Electromechanical braille displays, where little pins pop up or drop down to represent various characters, can cost upwards of a thousand dollars. That’s where the Modular Low-cost Braille Electro Display, aka MOLBED, steps up. The project’s creator, [Madaeon] aims to create a DIY-friendly, 3D-printable, and simple braille system. He’s working on a single character’s display, with the idea it could be expanded to cover a whole row or even offer multiple rows.

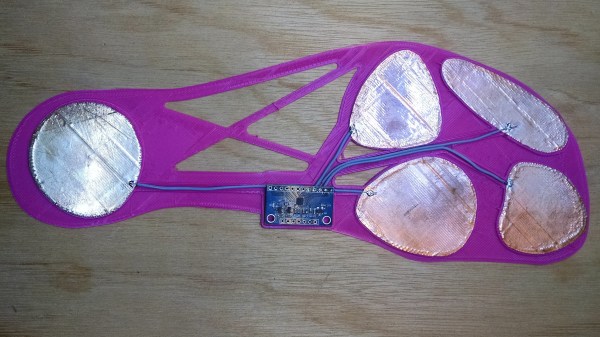

[Madeon]’s design involves using Flexinol actuator wire to control whether a pin sticks or not. He designed a “rocker” system consisting of a series of 6 pins that form the Braille display. Each pin is actuated by two Flexinol wires, one with current applied to it and one without, popping the pin up about a millimeter. Swap polarity and the pin pops down to be flush with the surface.

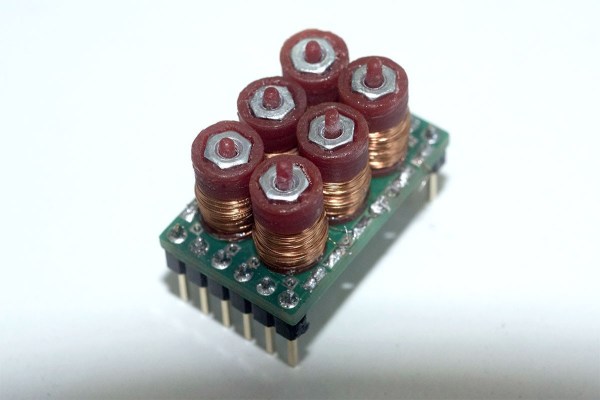

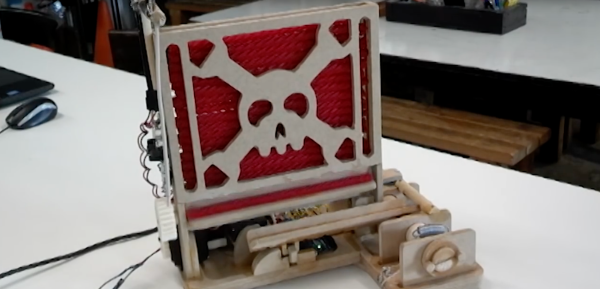

This project is actually [Madeon]’s second revision of the MOLBED system. The first version, an entry to the Hackaday Prize last year, used very small solenoids with two very small magnets at either end of the pole to hold the pin in place. The new system, while slightly more complex mechanically, should be easier to produce in a low-cost version, and has a much higher chance of bringing this technology to people who need it. It’s a great project, and a great entry to the Hackaday Prize.