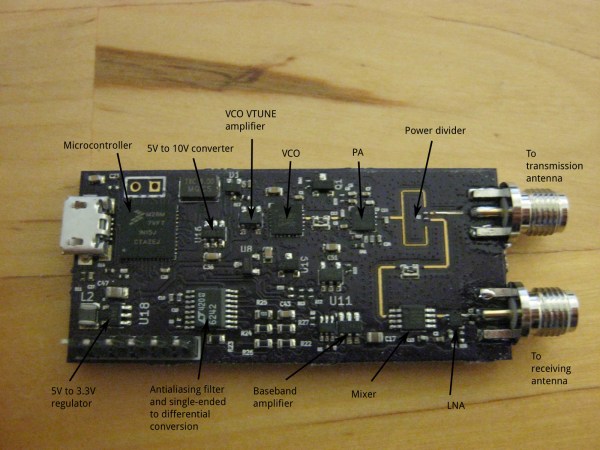

So you’ve built yourself an awesome radar system but it’s not performing as well as you had hoped. You assume this may have something to do with the tin cans you are using for antennas. The obvious next step is to design and build a horn antenna spec’d to work for your radar system. [Henrik] did exactly this as a way to improve upon his frequency modulated continuous wave radar system.

To start out, [Henrik] designed the antenna using CST software, an electromagnetic simulation program intended for this type of work. His final design consists of a horn shape with a 100mm x 85mm aperture and a length of 90mm. The software simulation showed an expected gain of 14.4dB and a beam width of 35 degrees. His old cantennas only had about 6dB with a width of around 100 degrees.

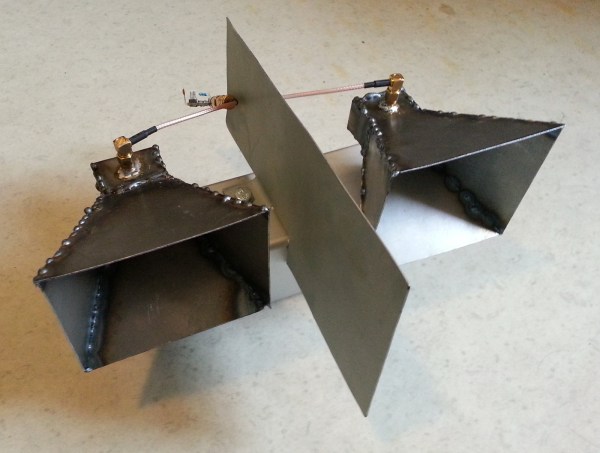

The two-dimensional components of the antenna were all cut from sheet metal. These pieces were then welded together. [Henrik] admits that his precision may be off by as much as 2mm in some cases, which will affect the performance of the antenna. A sheet of metal was also placed between the two horns in order to reduce coupling between the antennas.

[Henrik] tested his new antenna in a local football field. He found that his real life antenna did not perform quite as well as the simulation. He was able to achieve about 10dB gain with a field width of 44 degrees. It’s still a vast improvement over the cantenna design.

If you haven’t given Radar a whirl yet, check out [Greg Charvat’s] words of encouragement and then dive right in!