When it comes to electromagnetic waves, humans can really only directly perceive a very small part of the overall spectrum, which we call “visible light.” [rootkid] recently built an art piece that has perception far outside this range, turning invisible waves into a visible light sculpture.

The core of the device is the HackRF One. It’s a software defined radio (SDR) which can tune signals over a wide range, from 10 MHz all the way up to 6 GHz. [rootkid] decided to use the HackRF to listen in on transmissions on the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands. This frequency range was chosen as this is where a lot of devices in the home tend to communicate—whether over WiFi, Bluetooth, or various other short-range radio standards.

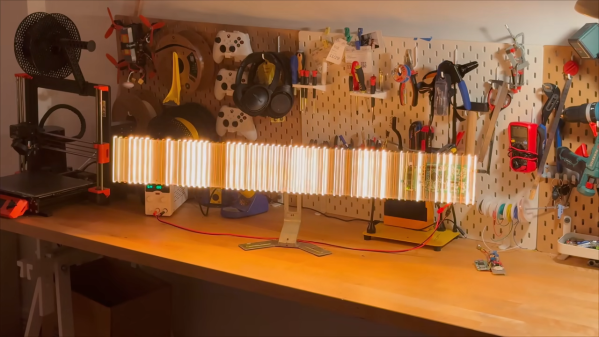

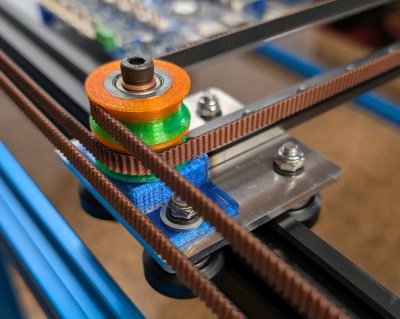

The SDR is hooked up to a Raspberry Pi Zero, which is responsible for parsing the radio data and using it to drive the light show. As for the lights themselves, they consist of 64 filament LEDs bent into U-shapes over a custom machined metal backing plate. They’re controlled over I2C with custom driver PCBs designed by [rootkid]. The result is something that looks like a prop from some high-budget Hollywood sci-fi. It looks even better when the radio waves are popping and the lights are in action.

It’s easy to forget about the rich soup of radio waves that we swim through every day.

Continue reading “Building A Light That Reacts To Radio Waves”