There was a time when a two-legged walking robot was the thing to make. But after seeing years of Boston Dynamic’s amazing four-legged one’s, more DIYers are switching to quadrupeds. Now we can add master DIY robot builder [James Bruton] to the list with his openDog project. What’s exciting here is that with [James’] extensive robot-building background, this is more like starting the challenge from the middle rather than the beginning and we should see exciting results sooner rather than later.

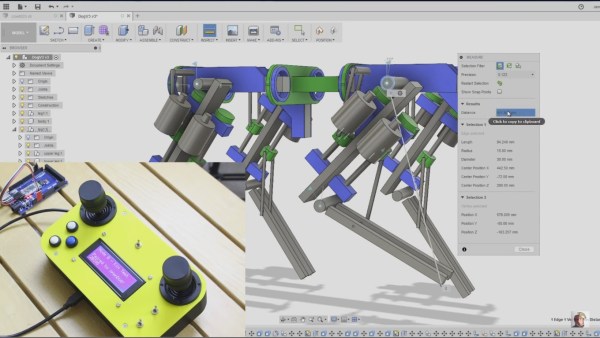

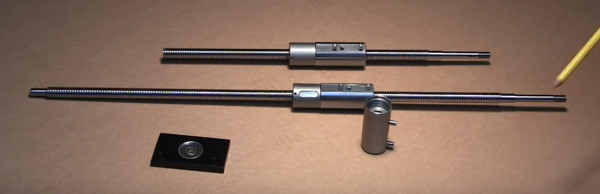

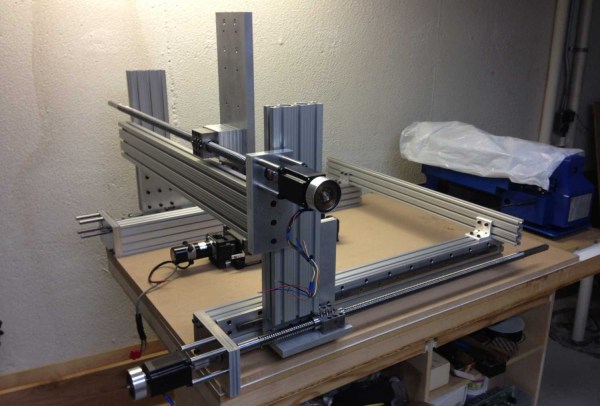

Thus far [James] has gone through the planning stage, having iterated through a few versions using Fusion 360, and he’s now purchased the parts. It’s going to be about the same size as Boston Robotic’s SpotMini and uses three motors for each leg. He considered going with planetary gearboxes on the motors but experienced a certain amount of play, or backlash, with them in his BB-9E project so this time he’s going with ball screws as he did with his exoskeleton. (Did we mention his extensive background?)

Each leg is actually made up of an upper and lower leg, which means his processing is going to have to include some inverse kinematics. That’s where the code decides where it wants the foot to go and then has to compute backwards from there how to angle the legs to achieve that. Again drawing from experience when he’s done it the hard way in the past, this time he’s designed the leg geometry to make those calculations easy. Having written up some code to do the calculations, he’s compared the computed angles with the measurements he gets from positioning the legs in Fusion 360 and found that his code is right on. We’re excited by what we’ve seen so far and bet it’ll be standing and walking in no time. Check out his progress in the video below.

Continue reading “[James Bruton] Is Making A Dog: OpenDog Project”