[Tarik and Kemal] have an objective in mind: to drop a home-made autonomous glider from a high-altitude balloon and safely return it to home. To motivate them, [Tarik] has decided not to cut his hair until they reach 18,000 feet. Given the ambition of their project, it isn’t surprising that his hair is getting rather long now.

drone392 Articles

The Drone That Flies In Any Orientation

Modern radio-controlled multi-rotor drone can be incredibly agile, but can only make orientation changes around the yaw axis while remaining in approximately the same position. Researchers at ETH Zurich have again built and tested multirotor with controllable motion six degrees of freedom, this time dramatically improving efficiency.

We covered a similar design from ETH Zurich previously which was hexacopter with arms with limited rotation. This new design is also a hexacopter, but with 2 coaxial motors on each rotating arm. Each arm has an increased range of rotation over the previous design, beyond 360 degrees. With the range of rotation and the very complex control system, the drone can efficiently fly in any orientation, while still being able to apply effective torque or linear force in any direction. This opens up a lot of possibilities for tasks that drones can perform, like close-up industrial inspection, using tools or pulling cables while keeping the rotors clear.

The arms do have a limited amount of rotation before winding the motor cable tight, but the control system keeps track of this and can unwind during or after movement. See the video after the break to see it in action. The complete scientific paper is not light reading, but definitely interesting. We’re looking forward to seeing if and when these type designs get used in real-world applications.

There are without a doubt a lot of drones in our future, and probably the most successful project to date is the Zipline fixed-wing drones in Rwanda and Ghana, which have made over 35000 deliveries of emergency medical supplies since 2016.

Thanks [Qes] for the tip!

The Drone That Can Play Dodgeball

Drones (and by that we mean actual, self-flying quadcopters) have come a long way. Newer ones have cameras capable of detecting fast moving objects, but aren’t yet capable of getting out of the way of those objects. However, researchers at the University of Zurich have come up with a drone that can not only detect objects coming at them, but can quickly determine that they’re a danger and get out of the way.

The drone has cameras and accompanying algorithms to detect the movement in the span of a couple of milliseconds, rather than the 20-40 milliseconds that regular quad-copters would take to detect the movement. While regular cameras send the entire screens worth of image data to the copter’s processor, the cameras on the University’s drone are event cameras, which use pixels that detect change in light intensity and only they send their data to the processor, while those that don’t stay silent.

Since these event cameras are a new technology, the quadcopter processor required new algorithms to deal with the way the data is sent. After testing and tweaking, the algorithms are fast enough that the ‘copter can determine that an object is coming toward it and move out of the way.

It’s great to see the development of new techniques that will make drones better and more stable for the jobs they will do. It’s also nice that one day, we can fly a drone around without worrying about the neighborhood kids lobbing basketballs at them. While you’re waiting for your quadcopter delivered goods, check out this article on a quadcopter testbed for algorithm development.

Drones Can Undertake Excavations Without Human Intervention

Researchers from Denmark’s Aarhus University have developed a method for autonomous drone scanning and measurement of terrains, allowing drones to independently navigate themselves over excavation grounds. The only human input is a starting location and the desired cliff face for scanning.

For researchers studying quarries, capturing data about gravel, walls, and other natural and man-made formations is important for understanding the properties of the terrain. Controlling the drones can be expensive though, since there’s considerable skill involved in manually flying the drone and keeping its camera steady and perpendicular to the wall it is capturing.

The process designed is a Gaussian model that predicts the wind encountered near the wall, estimating the strength based on the inputs it receives as it moves. It uses both nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) and a PID controller in its feedback control system, which calculate the values to send to the drone’s motor controller. A long short-term memory (LSTM) model is used for calculating the predictions. It’s been successfully tested in a chalk quarry in Denmark and will continue to be tested as its algorithms are improved.

Getting a drone to hover and move between GPS waypoints is easy enough, but once they need to maneuver around obstacles it starts getting tricky. Research like this will be invaluable for developing systems that help drones navigate in areas where their human operators can’t reach.

[Thanks to Qes for the tip!]

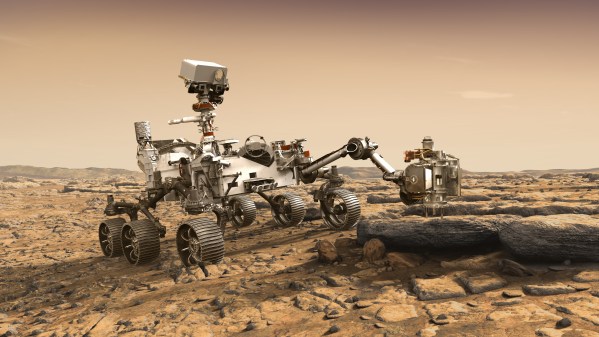

Mars 2020 Rover: Curiosity’s Hi-Tech Twin Is Strapped For Science; Includes A Flying Drone

While Mars may be significantly behind its sunward neighbor in terms of the number of motor vehicles crawling over its surface, it seems like we’re doing our best to close that gap. Over the last 23 years, humans have sent four successful rovers to the surface of the Red Planet, from the tiny Sojourner to the Volkswagen-sized Curiosity. These vehicles have all carved their six-wheeled tracks into the Martian dust, probing the soil and the atmosphere and taking pictures galore, all of which contribute mightily to our understanding of our (sometimes) nearest planetary neighbor.

You’d think then that sending still more rovers to Mars would yield diminishing returns, but it turns out there’s still plenty of science to do, especially if the dream of sending humans there to explore and perhaps live is to come true. And so the fleet of Martian rovers will be joined by two new vehicles over the next year or so, lead by the Mars 2020 program’s yet-to-be-named rover. Here’s a look at the next Martian buggy, and how it’s built for the job it’s intended to do.

Lego Drone Finally Takes Off

We were concerned when we saw [Brick Experiment Channel] test a drone propulsion pod made with Lego. After all, the thrust generated was less than the weight of the assembly. But a few tweaks got enough lift to overcome the assembly weight, as you can see in the video below.

The next step was to build three more pods and add some lightweight avionics and a battery. The first flight was a little dicey because the sensor orientation was off. Then there was some more software tuning before things really got airborne.

Hackaday Links: January 5, 2020

It looks like the third decade of the 21st century is off to a bit of a weird start, at least in the middle of the United States. There, for the past several weeks, mysterious squads of multicopters have taken to the night sky for reasons unknown. Witnesses on the ground report seeing both solo aircraft and packs of them, mostly just hovering in the night sky. In mid-December when the nightly airshow started, the drones seemed to be moving in a grid-search pattern, but that seems to have changed since then. These are not racing drones, nor are they DJI Mavics; witnesses report them to be 6′ (2 meters) in diameter and capable of staying aloft for 90 minutes. These are serious professional machines, not kiddies on a lark. So far, none of the usual government entities have taken responsibility for the flights, so speculation is all anyone has as to their nature. We’d like to imagine someone from our community will get out there with radio direction finding gear to locate the operators and get some answers.

We all know that water and electricity don’t mix terribly well, but thanks to the seminal work of White, Pinkman et al (2009), we also know that magnets and hard drives are a bad combination. But that didn’t stop Luigo Rizzo from using a magnet to recover data from a hard drive. He reports that the SATA drive had been in continuous use for more than 11 years when it failed to recover after a power outage. The spindle would turn but the heads wouldn’t move, despite several rounds of percussive maintenance. Reasoning that the moving coil head mechanism might need a magnetic jump-start, he probed the hard drive case with a magnetic parts holder until the head started moving again. He was then able to recover the data and retire the drive. Seems like a great tip to file away for a bad day.

It seems like we’re getting closer to a Star Trek future every day. No, we probably won’t get warp drives or transporters anytime soon, and if we’re lucky velour tunics and Spandex unitards won’t be making a fashion statement either. But we may get something like Dr. McCoy’s medical scanner thanks to work out of MIT using lasers to conduct a non-contact medical ultrasound study. Ultrasound exams usually require a transducer to send sound waves into the body and pick up the echoes from different structures, with the sound coupled to the body through an impedance-matching gel. The non-contact method uses pulsed IR lasers to penetrate the skin and interact with blood vessels. The pulses rapidly heat and expand the blood vessels, effectively turning them into ultrasonic transducers. The sound waves bounce off of other structures and head back to the surface, where they cause vibrations that can be detected by a second laser that’s essentially a sophisticated motion sensor. There’s still plenty of work to do to refine the technique, but it’s an exciting development in medical imaging.

And finally, it may actually be that the future is less Star Trek more WALL-E in the unlikely event that Segway’s new S-Pod personal vehicle becomes popular. The two-wheel self-balancing personal mobility device is somewhat like a sitting Segway, except that instead of leaning to steer it, the operator uses a joystick. Said to be inspired by the decidedly not Tyrannosaurus rex-proof “Gyrosphere” from Jurassic World, the vehicle tops out at 24 miles per hour (39 km/h). We’re not sure what potential market for these things would need performance like that – it seems a bit fast for the getting around the supermarket and a bit slow for keeping up with city traffic. So it’s a little puzzling, although it’s clearly easier to fully automate than a stand-up Segway.