For years it was a given that it was impossible to run a Linux based operating system on a less powerful computer whose architecture lacked a memory management unit. There were projects such as uCLinux which sought to provide some tidbits to low computing power Linux users, but ultimately they came to naught. It is achievable after a fashion though, by using the limited architecture to emulate a more powerful one. It’s been done on AVR chips emulating ARM, on ARM chips, and now someone’s done it on an ESP32-C3 microcontroller, a RISC-V part running a RISC-V emulator. What’s going on?

RISC-V is an architecture specification that can be implemented at many levels from a simple microcontroller or even a pile of 74 logic to a full-fat application processor. The ESP32-C3 lies towards the less complicated end of this curve, though that’s not the whole reason for the emulation. The PSRAM storage is used by the C3 as data storage and can’t be used to run software, so to access all that memory capacity an emulator is required that in turn can use the PSRAM as its program memory. It’s a necessary trick for Espressif’s implementation of the architecture.

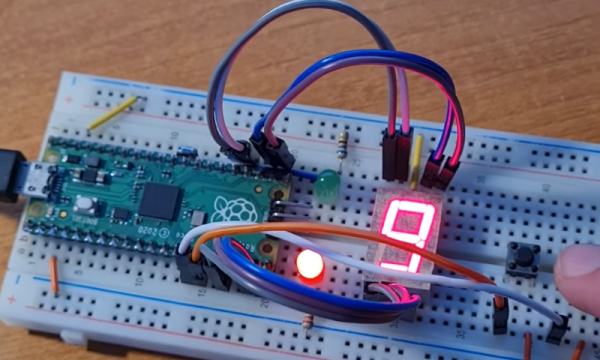

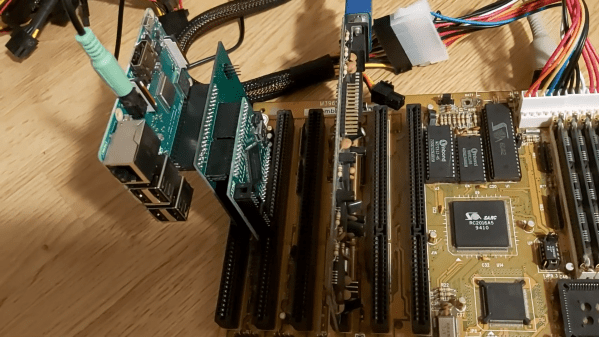

Surprisingly it’s not as slow as might be expected, with a boot-up time under two minutes. It’s not what we’d expect from our desktop powerhouses, but it’s not so long ago that certain lower-power full-fat processors could be just as lethargic. For past glories, see the AVR running Linux, and the RP2040.