Despite being a readily-available source of useful plastic, massive numbers of disposable bottles go to waste every day. To remedy this problem (or take advantage of this situation, depending on your perspective) [Igor Tylman] created the PETmachine, an extruder to make 3D printer filament from PET plastic bottles.

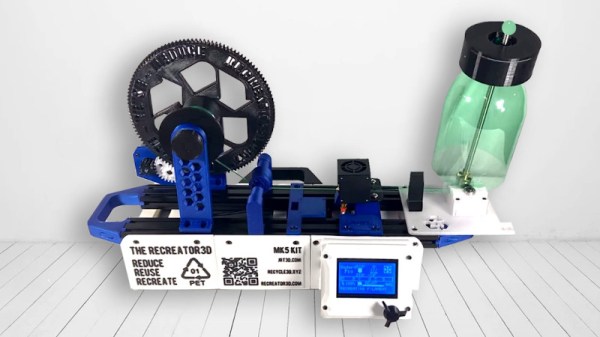

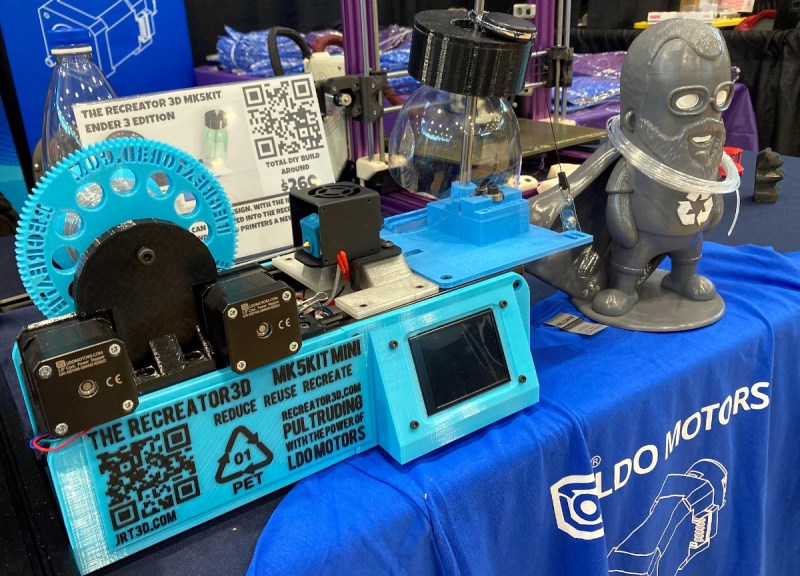

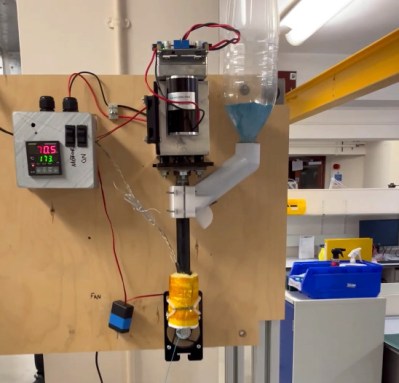

The design of the extruder is fairly standard for such machines: a knife mounted to the frame slices the bottle into one long strip, which feeds through a heated extruder onto a spool which pulls the plastic strand through the system. This design stands out, though, in its documentation and ease of assembly. The detailed assembly guides, diagrams, and the lack of crimped or soldered connections all make it evident that this was designed to be built in a classroom. The filament produced is of respectable quality: 1.75 mm diameter, usually within a tolerance of 0.05 mm, as long as the extruder’s temperature and the spool’s speed were properly calibrated. However, printing with the filament does require an all-metal hotend capable of 270 ℃, and a dual-drive extruder is recommended.

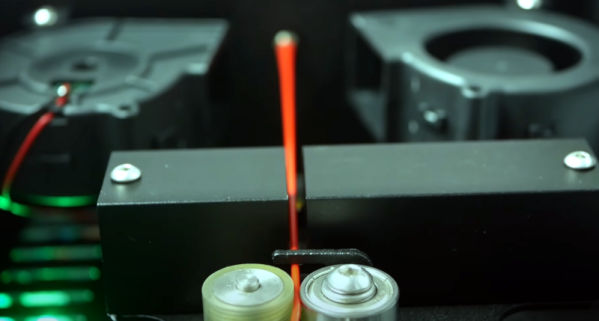

One issue with the extruder is that each bottle only produces a short strand of filament, which isn’t sufficient for printing larger objects. Thus, [Igor] also created a filament welder and a spooling machine. The welder uses an induction coil to heat up a steel tube, inside of which the ends of the filament sections are pressed together to create a bond. The filament winder, for its part, can wind with adjustable speed and tension, and uses a moving guide to distribute the filament evenly across the spool, avoiding tangles.

If you’re interested in this kind of extruder, we’ve covered a number of similar designs in the past. The variety of filament welders, however, is a bit more limited.

Thanks to [RomanMal] for the tip!