A bunch of audio heads over at the Head-Fi forum were discussing handy and quick heat sinking methods, leading to much speculation and conjecture. This finally prompted [tangentsoft] to take matters in his own hands and run some tests on DIY Heat Sinks.

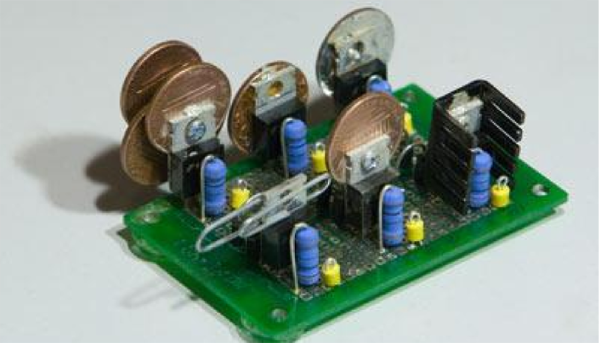

The question that sparked this debate was if a paper clip is a good enough heat sink to be used for a TO220 package. Some folks suggested copper pennies (old ones minted 1981 and earlier – the new ones are zinc with copper plating and won’t help much). [tangentsoft] built a jig to test six LM317 regulators in constant current mode set to 0.125A and 2w dissipation. The six configurations were a paper clip, a single penny bolted to the regulator, a regular Aavid TO220 heat sink, a set of 4 pennies bolted, a single penny epoxy glued and finally a single penny soldered directly to the regulator.

The results were pretty interesting. The paper clip scored better than any of the single pennies! The quad-penny and the Aavid heat sink fared above all the other configurations, and almost at par with each other. [tangentsoft] posts his review of each configurations performance and also provides details of his test method, in case someone else wants to replicate his tests to corroborate the results. He tested each configuration independently for one hour, gathering just over 10000 readings for each setup. Other nearby heat sources were turned off, and he placed strategic barriers around the test circuit to isolate it from the effects of other cooling / heating sources. He even removed himself from the test area and monitored his data logging remotely from another room. When he noticed a couple of suspect deviations, he restarted the test.

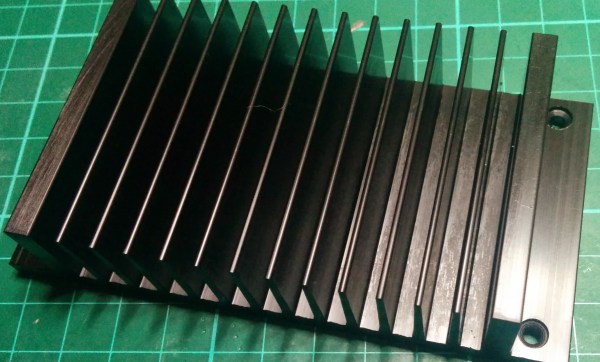

[tangentsoft] put all the data through Mathematica and plotted his results for analysis, available at this link [pdf, 2.8MB]. So the next time you want to heat sink a regulator for cheap, just hunt for Clippy in your box of office supplies. Do remember that these methods will work for only a couple of watts dissipation. If you would like to cast and build your own heat sinks out of aluminum, check out this post about DIY Aluminum heat sink casting. And if you need help calculating heat sink parameters, jump to 12:00 minutes in this video from [Dave]’s EEVBlog episode on Dummy loads and heat sinks.

Thanks to [Greg] for sending in this tip.

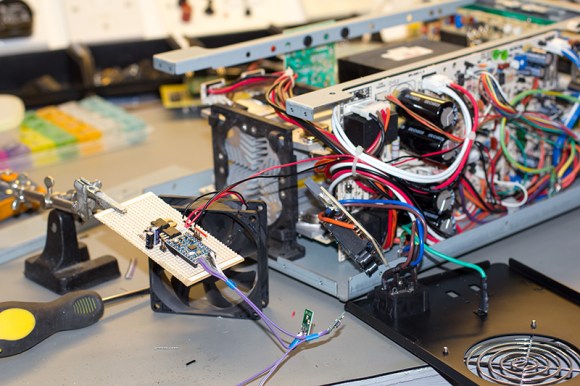

[Brian] adores his GW Instek GPC-1850D power supply, but it’s annoyingly loud and disruptive to his audio projects. The thing works great, so he decided to

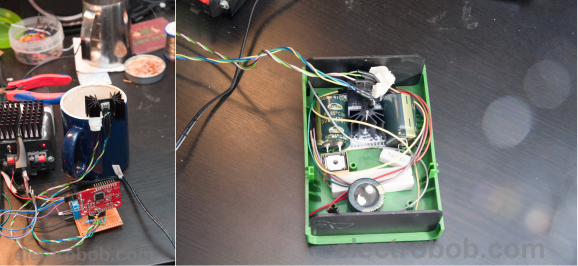

[Brian] adores his GW Instek GPC-1850D power supply, but it’s annoyingly loud and disruptive to his audio projects. The thing works great, so he decided to  [Bogdan] knows that it’s hard to model the cooling needs of any given project. It’s important to know how much heat a system can dissipate given the housing material, airflow opportunity, and the proximity of neighboring components. Inspired by an aluminium-walled enclosure that allows for mounted transistors,

[Bogdan] knows that it’s hard to model the cooling needs of any given project. It’s important to know how much heat a system can dissipate given the housing material, airflow opportunity, and the proximity of neighboring components. Inspired by an aluminium-walled enclosure that allows for mounted transistors,