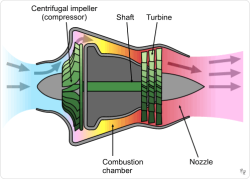

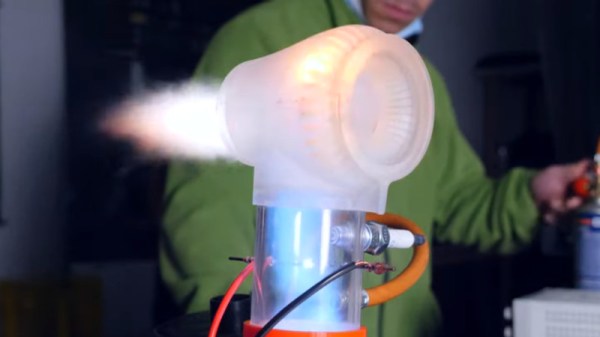

Have you ever wished you could peer inside a complex machine while it was still running? We sort of can with simulations and the CAD tools we have today, but it isn’t the same as doing IRL. [Warped Perception] made a see-thru jet engine to experience the feeling. The effect, we dare say, is better than any simulation.

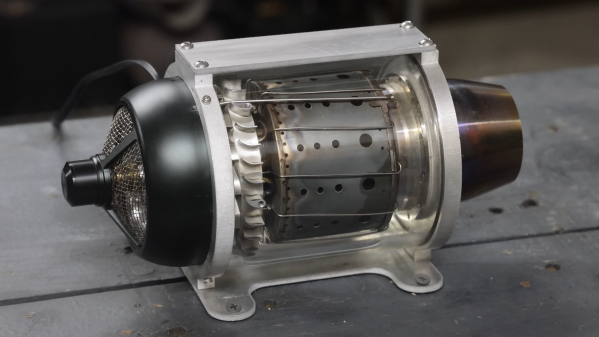

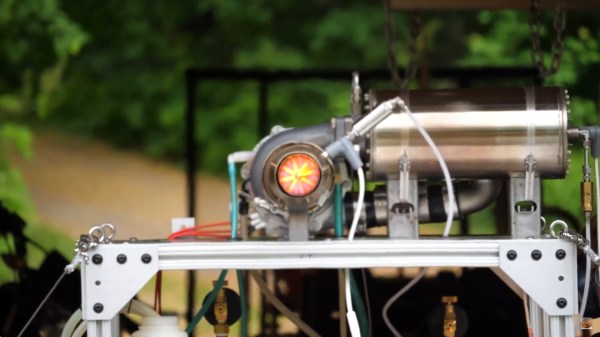

[Warped Perception] has a good bit of experience with jet engines and previously mounted them to his car. The first step was balancing, and while he didn’t use an oscilloscope, he could get it within a few thousands of a gram balanced. Then, after some light CAD work, it was all machining. Brackets were fabricated, and gaskets were laser cut to hold the large thick clear cover together. There are a few exciting things to see (and hear). The engine expands and contracts significantly due to pressure and heat, but it’s interesting to see it move physically as it ramps up and down.

Additionally, the sound as it goes through the various thrust levels is quite impressive. But, of course, what’s a jet engine test with an airflow test? Surprisingly, the engine didn’t pull in as much air as he thought. Eighty pounds of thrust doesn’t mean eighty pounds of air.

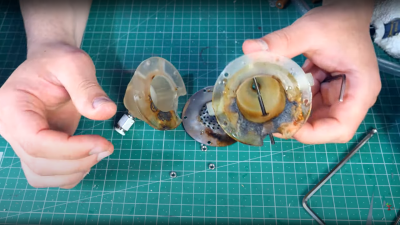

This 3D-printed water-cooled jet engine isn’t quite see-through, but it is interesting to see the thorough process of making the engine itself. Video after the break.