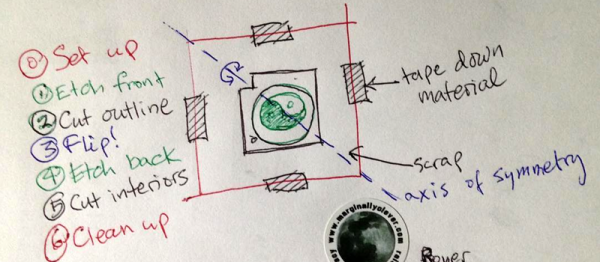

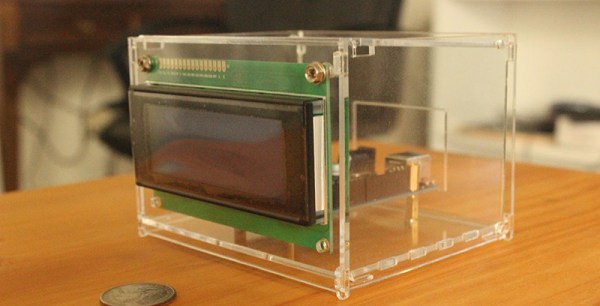

[Dan Royer] explains a simple method to engrave/etch on both sides of a material. This could be useful when you are trying to build enclosures or boxes which might need markings on both sides. There are two hurdles to overcome when doing this. The first is obviously registration. When you flip your job, you want it re-aligned at a known datum/reference point.

The other is your flip axis. If the object is too symmetric, it’s easy to make a mistake here, resulting in mirrored or rotated markings on the other side. Quite simply, [Dan]’s method consists of creating an additional cutting edge around your engraving/cutting job. This outline is such that it provides the required registration and helps flip the job along the desired axis.

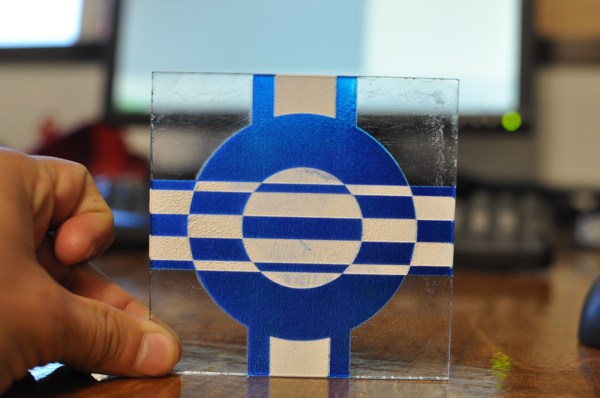

You begin by taping down your work piece on the laser bed. Draw a symmetrical shape around the job you want to create in your Laser Cutter software of choice. The shape needs to have just one axis of symmetry – this rules out squares, rectangles or circles – all of which have multiple axes of symmetry. Adding a single small notch in any of these shapes does the trick. Engrave the back side. Then cut the “outside” outline. Lift the job out and flip it over. Engrave the front side. Cut the actual outline of your job and you’re done.

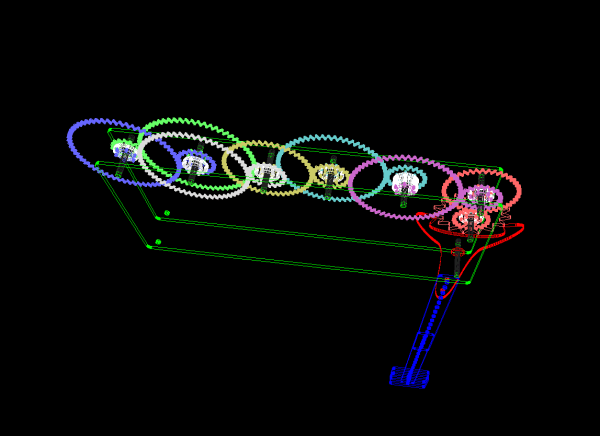

Obviously, doing all this requires some preparation in software. You need the back engrave layer, the front engrave layer, the job cut outline and the registration cut outline. Use color coded pen settings in a drawing to create these layers and the horizontal / vertical mirror or flip commands. These procedures aren’t groundbreaking, but they simplify and nearly automate a common procedure. If you have additional tricks for using laser cutters, chime in with your comments here.