One of the most powerful features of Unix and Linux is that using traditional command line tools, everything is a stream of bytes. Granted, modern software has blurred this a bit, but at the command line, everything is text with certain loose conventions about what separates fields and records. This lets you do things like take a directory listing, sort it, remove the duplicates, and compare it to another directory listing. But what if the shell understood more data types other than streams? You might argue it would make some things better and some things worse, but you don’t have to guess, you can install cosh, a shell that provides tools to produce and work with structured data types.

The system is written with Rust, so you will need Rust setup to compile it. For most distributions, that’s just a package install (rust-all in Ubuntu-like distros, for example). Once you have it running, you’ll have a few new things to learn compared to other shells you’ve used. Continue reading “Linux Fu: The Shell Forth Programmers Will Love”

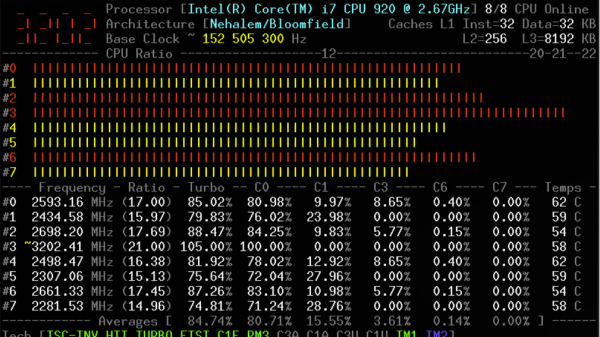

The tool relies on a kernel module, and is coded primarily in C, with some assembly code used to measure performance as accurately as possible. It’s capable of reporting everything from core frequencies to details on hyper-threading and turbo boost operation. Other performance reports include information on instructions per cycle or instructions per second, and of course, all the thermal monitoring data you could ask for. It all runs in the terminal, which helps keep overheads low.

The tool relies on a kernel module, and is coded primarily in C, with some assembly code used to measure performance as accurately as possible. It’s capable of reporting everything from core frequencies to details on hyper-threading and turbo boost operation. Other performance reports include information on instructions per cycle or instructions per second, and of course, all the thermal monitoring data you could ask for. It all runs in the terminal, which helps keep overheads low.