As reported by The Register, hackers can now listen in on conversations happening around your computer by turning a hard drive into a microphone. There are caveats: the hack only works if these conversations are twice as loud as a blender, or about as loud as a lawn mower. In short, no one talks that loud, move along, nothing to see here.

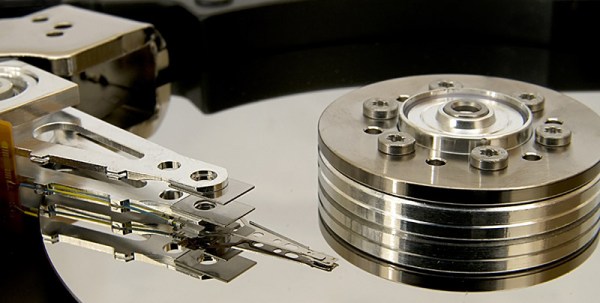

The attack is to be presented at the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, and describes the attack as a modification of the firmware on a disk drive to read the Position Error Signal that keeps read/write heads in the optimal position. This PES is affected by air pressure, and if something is affected by air pressure, you’ve got a microphone. In this case, it’s a terrible microphone that’s mechanically coupled to a machine that has a lot of vibrations including the spinning platter and a bunch of fans inside the computer. This is an academic exercise, and not a real attack, and either way to exfiltrate this data you need to root the computer the hard drive is attached to. It’s attacks all the way down.

The limiting factor in this attack is that it requires a very loud conversation to be held near a hard drive. To record speech, the researchers had to pump up the volume to 85 dBA, or about the same volume as a blender crushing some ice. Recording music through this microphone so that Shazam could identify the track meant playing the track back at 90 dBA, or about the same volume as a lawnmower. Basically, this isn’t happening.

The interesting bit of this hack isn’t using a hard drive as a microphone. It’s modifying the firmware on a hard drive to do something. We’ve seen some hacks like this before, but the latest public literature on hard drive firmware hacking is years old. If you’ve got a tip on how to hack hard drives, even if it’s to do something that’s horribly impractical, we’d love to see it.