The first thing I ever built without a kit was a 5 V regulated power supply using the old LM309K. That’s a classic linear regulator like a 7805. While they are simple, they waste a lot of energy as heat, especially if the input voltage goes higher. While there are still applications where linear regulators make sense, they are increasingly being replaced by switching power supplies that are much more efficient. How do switchers work? Well, you buy a switching power supply IC, add an inductor and you are done. Class dismissed. Oh wait… while that might be the best way to do it from a cost perspective, you don’t really learn a lot that way.

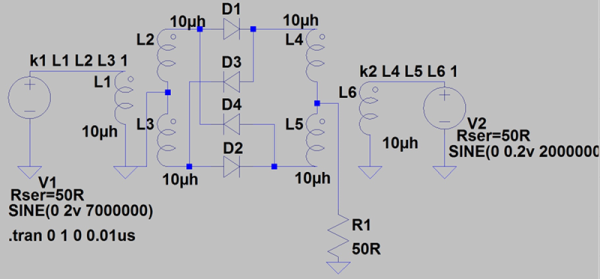

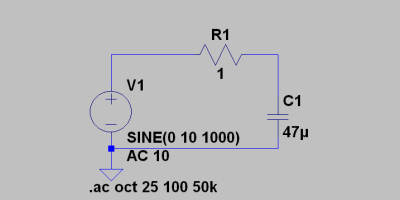

In this installment of Circuit VR, we’ll look at a simple buck converter — that is a switching regulator that takes a higher voltage and produces a lower voltage. The first one won’t actually regulate, mind you, but we’ll add that in a future installment. As usual for Circuit VR, we’ll be simulating the designs using LT Spice.

Interestingly, LT Spice is made to design power supplies so it has a lot of Linear Technology parts in its library just for that purpose. However, we aren’t going to use anything more sophisticated than an op amp. For the first pass, we won’t even be using those.