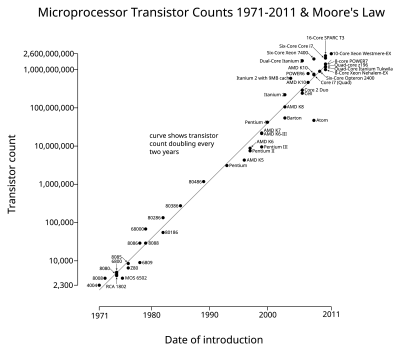

Sad news in the tech world this week as Intel co-founder Gordon Moore passed away in Hawaii at the age of 94. Along with Robert Noyce in 1968, Moore founded NM Electronics, the company that would later go on to become Intel Corporation and give the world the first commercially available microprocessor, the 4004, in 1971. The four-bit microprocessor would be joined a few years later by the 8008 and 8080, chips that paved the way for the PC revolution to come. Surprisingly, Moore was not an electrical engineer but a chemist, earning his Ph.D. from the California Institute of Technology in 1954 before his postdoctoral research at the prestigious Applied Physics Lab at Johns Hopkins. He briefly worked alongside Nobel laureate and transistor co-inventor William Shockley before jumping ship with Noyce and others to found Fairchild Semiconductor, which is where he made the observation that integrated circuit component density doubled roughly every two years. This calculation would go on to be known as “Moore’s Law.”

moore’s law Articles

Gordon Moore, 1929 — 2023

The news emerged yesterday that Gordon Moore, semiconductor pioneer, one of the founders of both Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, and the originator of the famous Moore’s Law, has died. His continuing influence over all aspects of the technology which makes our hardware world cannot be overstated, and his legacy will remain with us for many decades to come.

A member of the so-called “Traitorous Eight” who left Shockley Semiconductor in 1957 to form Fairchild Semiconductor, he and his cohort laid the seeds for what became Silicon Valley and the numerous companies, technologies, and products which have flowed from that. His name is probably most familiar to us through “Moore’s Law,” the rate of semiconductor development he first postulated in 1965 and revisited a decade later, that establishes a doubling of integrated circuit component density every two years. It’s a law that has seemed near its end multiple times over the decades since, but successive advancements in semiconductor fabrication technology have arrived in time to maintain it. Whether it will continue to hold from the early 2020s onwards remains a hotly contested topic, but we’re guessing its days aren’t quite over yet.

Perhaps Silicon Valley doesn’t hold the place in might once have in the world of semiconductors, as Uber-for-cats app startups vie for attention and other semiconductor design hubs worldwide steal its thunder. But it’s difficult to find a piece of electronic technology, whether it was designed in Mountain View, Cambridge, Shenzhen, or wherever, that doesn’t have Gordon Moore and the rest of those Fairchild founders in its DNA somewhere. Our world is richer for their work, and that’s what we’ll remember Gordon Moore for.

You can read our thoughts on Moore’s famous law. If you ever wondered how Silicon Valley became the place for electronics, the story is probably much older than you think.

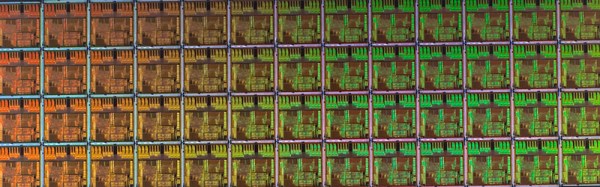

Smaller Is Sometimes Better: Why Electronic Components Are So Tiny

Perhaps the second most famous law in electronics after Ohm’s law is Moore’s law: the number of transistors that can be made on an integrated circuit doubles every two years or so. Since the physical size of chips remains roughly the same, this implies that the individual transistors become smaller over time. We’ve come to expect new generations of chips with a smaller feature size to come along at a regular pace, but what exactly is the point of making things smaller? And does smaller always mean better?

Smaller Size Means Better Performance

Over the past century, electronic engineering has improved massively. In the 1920s, a state-of-the-art AM radio contained several vacuum tubes, a few enormous inductors, capacitors and resistors, several dozen meters of wire to act as an antenna, and a big bank of batteries to power the whole thing. Today, you can listen to a dozen music streaming services on a device that fits in your pocket and can do a gazillion more things. But miniaturization is not just done for ease of carrying: it is absolutely necessary to achieve the performance we’ve come to expect of our devices today. Continue reading “Smaller Is Sometimes Better: Why Electronic Components Are So Tiny”

Moore’s Law Is Over (Again)

According to this article in Nature, Moore’s Law is officially done. And bears poop in the woods.

There was a time, a few years back, when the constant exponential growth rate of the number of transistors packed into an IC was taken for granted: every two years, a doubling in density. After all, it was a “law” proposed by Gordon E. Moore, founder of Intel. Less a law than a production goal for a silicon manufacturer, it proved to be a very useful marketing gimmick.

Rumors of the death of Moore’s law usually stir up every couple years, and then Intel would figure out a way to pack things even more densely. But lately, even Intel has admitted that the pace of miniaturization has to slow down. And now we have confirmation in Nature: the cost of Intel continuing its rate of miniaturization is less than the benefit.

We’ve already gotten used to CPU speed increases slowing way down in the name of energy efficiency, so this isn’t totally new territory. Do we even care if the Moore’s-law rate slows down by 50%? How small do our ICs need to be?

Graph by [Wgsimon] via Wikipedia.

Exponential Growth In Linear Time: The End Of Moore’s Law

Moore’s Law states the number of transistors on an integrated circuit will double about every two years. This law, coined by Intel and Fairchild founder [Gordon Moore] has been a truism since it’s introduction in 1965. Since the introduction of the Intel 4004 in 1971, to the Pentiums of 1993, and the Skylake processors introduced last month, the law has mostly held true.

The law, however, promises exponential growth in linear time. This is a promise that is ultimately unsustainable. This is not an article that considers the future roadblocks that will end [Moore]’s observation, but an article that says the expectations of Moore’s Law have already ended. It ended quietly, sometime around 2005, and we will never again see the time when transistor density, or faster processors, more capable graphics cards, and higher density memories will double in capability biannually.

Continue reading “Exponential Growth In Linear Time: The End Of Moore’s Law”

Moore’s Law Of Raspberry Pi Clusters

[James J. Guthrie] just published a rather formal announcement that his 4-node Raspberry Pi cluster greatly outperforms a 64-node version. Of course the differentiating factor is the version of the hardware. [James] is using the Raspberry Pi 2 while the larger version used the Model B.

We covered that original build almost three years ago. It’s a cluster called the Iridris Pi supercomputer. The difference is a 700 MHz single core versus the 900 Mhz quad-core with double-the ram. This let [James] benchmark his four-node-wonder at 3.048 gigaflops. You’re a bit fuzzy about what a gigaflops is exactly? So were we… it’s a billion floating point operations per second… which doesn’t matter to your human brain. It’s a ruler with which you can take one type of measurement. This is triple the performance at 1/16th the number of nodes. The cost difference is staggering with the Iridris ringing in at around £2500 and the light-weight 4-node built at just £120. That’s more than an order of magnitude.

Look, there’s nothing fancy to see in [James’] project announcement. Yet. But it seems somewhat monumental to stand back and think that a $35 computer aimed at education is being used to build clusters for crunching Ph.D. level research projects.