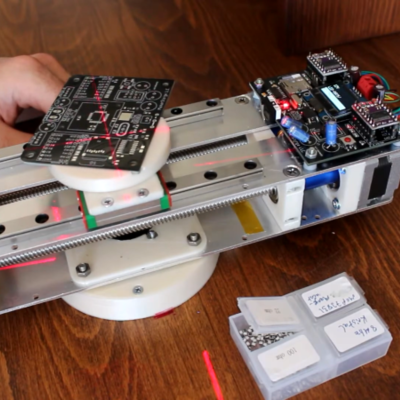

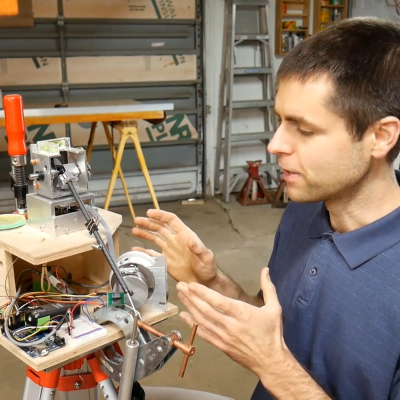

In the winter, I hatched a vague plan to learn some of the modern unmanned aerial vehicle tech. Everybody needs an autonomous vehicle, and we’ve got some good flying fields within walking distance, so it seemed like it could work. Being me, that meant buying the cheapest gear that could possibly work, building up the plane by myself, and generally figuring out as much as possible along the way. I learn more by making my own mistakes anyway. Sounds like a good summer project.

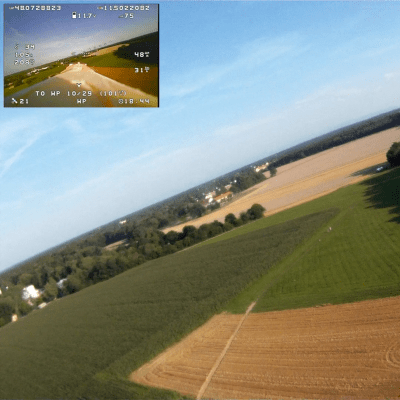

Fast-forward to August, and the plane is built, controller installed, and I’ve spent most of the last month trying to make them work well together. (The firmware expects a plane with ailerons, and mine doesn’t have them, but apparently I’d rather tweak PID values than simply add a couple wing servos.) But it’s working well enough that it’s launching, flying autonomous waypoint missions, and coming home without any intervention. So, mission accomplished, right?

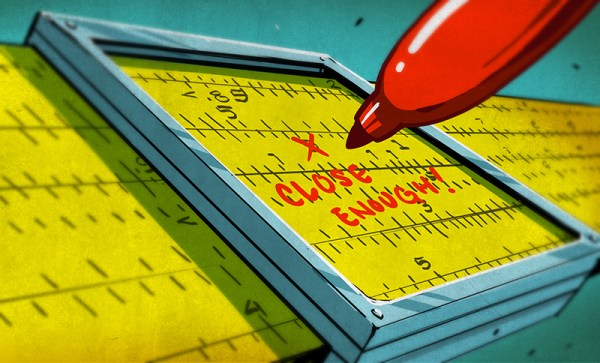

Nope. When I’m enjoying a project, I have a way of moving the goalposts on myself. I mean, I don’t really want to be done anyway. When a friend asked me a couple weeks ago what I was planning to do with the plane, I said “take nice aerial videos of that farm over there.” Now I see flight opportunities everywhere, and need to work on my skills. The plane needed an OLED display. It probably still needs Bluetooth for local configuration as well. Maybe a better long-range data link…

This is creeping featurism and moving-the-goalposts in the best of ways. And if this were a project with a deadline, or one that I weren’t simply enjoying, it would be a problem. Instead, having relatively low-key goals, meeting them, and letting them inspire me to set the next ones has been a blast. It makes me think of Donald Papp’s great article on creating hacking “win” projects. There he suggests creating simple goals to keep yourself inspired. I don’t think I could have planned out an “optimal” set of goals to begin with — I’ve learned too much along the way that the next goal isn’t obvious until I know what new capabilities I have. Creeping is the only way.

What about you? Do you plan your hobby projects completely in advance? Not at all? Or do you have some kind of hybrid, moving-the-goalposts sort of strategy?