In 1985, [Wim van Eck] published several technical reports on obtaining information the electromagnetic emissions of computer systems. In one analysis, [van Eck] reliably obtained data from a computer system over hundreds of meters using just a handful of components and a TV set. There were obvious security implications, and now computer systems handling highly classified data are TEMPEST shielded – an NSA specification for protection from this van Eck phreaking.

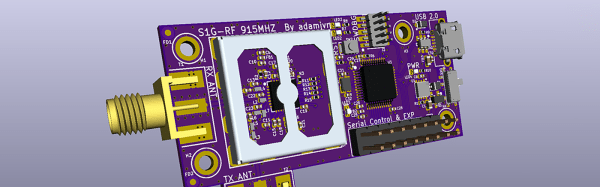

Methods of van Eck phreaking are as numerous as they are awesome. [Craig Ramsay] at Fox It has demonstrated a new method of this interesting side-channel analysis using readily available hardware (PDF warning) that includes the ubiquitous RTL-SDR USB dongle.

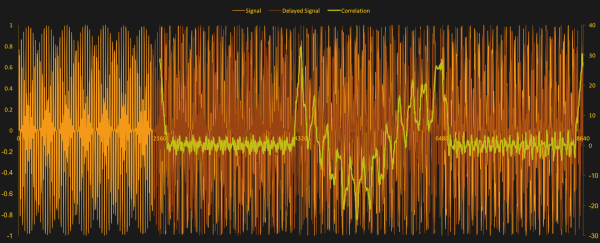

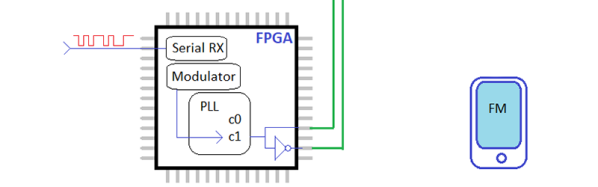

The experimental setup for this research involved implementing AES encryption on two FPGA boards, a SmartFusion 2 SOC and a Xilinx Pynq board. After signaling the board to run its encryption routine, analog measurement was performed on various SDRs, recorded, processed, and each byte of the key recovered.

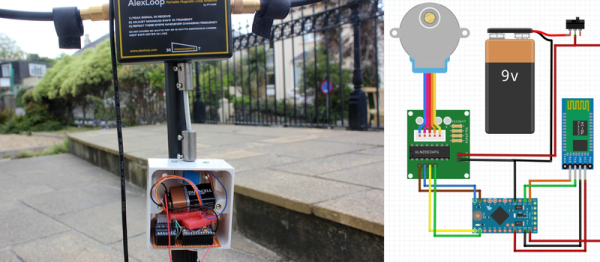

The results from different tests show the AES key can be extracted reliably in any environment, provided the antenna is in direct contact with the device under test. Using an improvised Faraday cage constructed out of mylar space blankets, the key can be reliably extracted at a distance of 30 centimeters. In an anechoic chamber, the key can be extracted over a distance of one meter. While this is a proof of concept, if this attack requires direct, physical access to the device, the attacker is an idiot for using this method; physical access is root access.

However, this is a novel use of software defined radio. As far as the experiment itself is concerned, the same result could be obtained much more quickly with a more relevant side-channel analysis device. The ChipWhisperer, for example, can extract AES keys using power signal analysis. The ChipWhisperer does require a direct, physical access to a device, but if the alternative doesn’t work beyond one meter that shouldn’t be a problem.