As if the war in Ukraine weren’t bad enough right here on Earth, it threatens knock-on effects that could be felt as far away as Mars. One victim of the deteriorating relationships between nations is the next phase of the ExoMars project, a joint ESA-Roscosmos mission that includes the Rosalind Franklin rover. The long-delayed mission was most recently set for launch in October 2022, but the ESA says that hitting the narrow launch window is now “very unlikely.” That’s a shame, since the orbital dynamics of Earth and Mars will mean that it’ll be 2024 before another Hohmann Transfer window opens. There are also going to be repercussions throughout the launch industry due to Russia pulling the Soyuz launch team out of the ESA’s spaceport in Guiana. And things have to be mighty tense aboard the ISS right about now, since the station requires periodic orbital boosting with Russian Progress rockets.

railway30 Articles

Building Switching Points For A Backyard Railway

A home-built railway is one of the greatest things you could possibly use to shift loads around your farm. [Tim] and [Sandra] of YouTube channel [Way Out West] have just such a setup, but they needed some switching points to help direct carriages from one set of rails to another. Fabrication ensued!

The railway relies on very simple rails made with flat bar and angle iron, allowing the railway to be built without a lot of heavy blacksmithing work. For a light-duty home railway, these are more than strong enough to do the job.

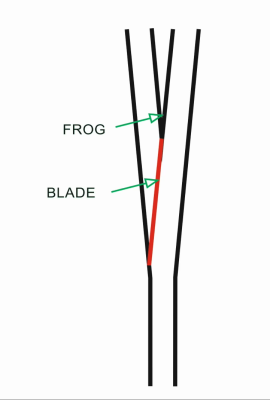

As for the points, a simple V-shaped frog-and-blade design was used. The frog is the V-shaped section where the rails diverge into two directions, sitting in the center of the Y, while the blade is the part that moves to either side to guide the carriages in one way or t’other.

The blade consists of a 2.2 meter long piece of angle iron with a pin welded on, allowing it to pivot. Two pieces of flat bar were then welded together with a pin to make the frog. Two metal bushes were then forced into a wooden sleeper, allowing the blade to pivot as needed. The rails themselves are slightly kinked as needed and everything tacked down into sleepers with bolts and pipe pegs.

The design runs smoothly, much to [Tim]’s enjoyment. It’s a clear improvement over the earlier design we looked at least year.

There’s something inherently charming about a railway built with little more than wood, metal, and hammers. Seeing the little stone wagon run down the rails to bed in the sleepers is utterly joyful in a way that’s difficult to fully explain. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Building Switching Points For A Backyard Railway”

You Too Can Be A Railroad Baron!

It’s likely that among our readers are more than a few who hold an affection for trains. Whether you call them railroads or railways they’re the original tech fascination, and it’s no accident that the word Hacker was coined at MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club. So some of you like us watch locomotive YouTube videos, others maybe have an OO layout tucked away somewhere, and still more cast an eye at passing trains wishing they were aboard. Having a proper railway of one’s own remains a pipe-dream, but perhaps a hardcore rail enthusiast might like to take a look at [Way Out West Blow-in blog’s] video series on building a farm railway.

On a smallholding there is always a lot to be moved around, and frequently not the machinery with which to do it. Using a wheelbarrow or handcart on rough ground is as we can attest, back-breaking, so there’s a real gap in the market for anything to ease the task. So a railway becomes an attractive solution, assuming that its construction cost isn’t prohibitive.

The videos below the break are the first two of what will no doubt become a lengthy series, and deals with the construction of the rails themselves including the sleepers cut with a glorious home-made band saw, and then fishplates and a set of rudimentary points. The rails themselves are off-the-shelf flat steel strip laid upon its edge, and secured to the sleepers by short lengths of galvanized tube. It’s clear this isn’t a railroad in the sense that we might understand it, indeed though it uses edge rail it has more in common for its application with some early mining plateways But assuming that the flat strip rail doesn’t twist we can see that it should be perfectly adequate for hand-driven carts, removing the backbreaking aspect of their moving. It will be interesting to follow this project down the line.

Farm railways haven’t featured on Hackaday before, but your inner rail enthusiast might be sated by the world’s first preserved line.

Hackaday Links: January 31, 2021

There are an awful lot of machines on the market these days that fall under the broad category of “cheap Chinese laser cutters”. You know the type — the K40s, the no-name benchtop CO2 cutters, the bigger floor-mount units. If you’ve recently purchased one of these machines from one of the usual vendors, or even if you’re just thinking about doing so, you’ll likely have some questions. In which case, this “Chinese Laser Cutters 101” online class might be right up your alley. We got wind of this though its organizer, Jonathan Schwartz of American Laser Cutter in Los Angeles, who says he’s been installing, repairing, and using laser cutters for a decade now. The free class will be on February 8 at 5:00 PM PST, and while it’s open to all, it does require registration.

We got an interesting tip the other day that had to do with Benford’s Law. We’d never heard of this one, so we assumed was a “joke law” like Murphy’s Law or Betteridge’s Rule of Headlines. But it turns out that Benford’s Law describes the distribution of leading digits in large sets of numbers. Specifically, it says that the leading digit in any given number is more likely to be one of the smaller numbers. Measurements show that rather than each of the nine base 10 digits showing up about 11% of the time, a 1 will appear in the leading digit 30% of the time, while a 9 will appear about 5% of the time. It’s an interesting phenomenon, and the tip we got pointed to an article that attempted to apply Benford’s Law to image files. This technique was used in a TV show to prove an image had been tampered with, but as it turns out, Hollywood doesn’t always get technical material right. Shocking, we know, but the technique was still interesting and the code developed to Benford-ize image files might be useful in other ways.

Everyone knew it was coming, and for a long time in advance, but it still seems that the once-and-for-all, we’re not kidding this time, it’s for realsies shutdown of Adobe Flash has had some real world consequences. To wit, a railroad system in the northern Chinese city of Dalian ground to a halt earlier this month thanks to Flash going away. No, they weren’t using Flash to control the railroad, but rather it was buried deep inside software used to schedule and route trains. It threw the system into chaos for a while, but never fear — they got back up and running by installing a pirated version of Flash. Here’s hoping that they’re working on a more permanent solution to the problem.

First it was toilet paper and hand sanitizer, now it’s…STM32 chips? Maybe, if the chatter on Twitter and other channels is to be believed. Seems like people are having a hard time sourcing the microcontroller lately. It’s all anecdotal so far, of course, but the prevailing theory is that COVID-19 and worker strikes have lead to a pinch in production. Plus, you know, the whole 2020 thing. We’re wondering if our readers have noticed anything on this — if so, let us know in the comments below.

And finally, just because it’s cool, here’s a video of what rockets would look like if they were transparent. Well, obviously, they’d look like twisted heaps of burning wreckage on the ground is they were really made with clear plastic panels and fuel tanks, but you get the idea. The video launches a virtual fleet — a Saturn V, a Space Shuttle, a Falcon Heavy, and the hypothetical SLS rocket — and flies them in tight formation while we get to watch their consumables be consumed. If the burn rates are accurate, it’s surprising how little fuel and oxidizer the Shuttle used compared to the Saturn. We were also surprised how long the SLS holds onto its escape tower, and were pleased by the Falcon Heavy payload reveal.

Hyperloop: Fast, But At What Cost?

When it comes to travelling long distances, Americans tend to rely on planes, while the Chinese and Europeans love their high speed rail. However, a new technology promises greater speed with lower fares, with fancy pods travelling in large tubes held at near-vacuum pressures. It goes by the name of Hyperloop.

Spawned from an “alpha paper” put together by Elon Musk in 2013, the technology is similar to other vactrain systems proposed in the past. Claiming potential top speeds of up to 760 mph, Hyperloop has been touted as a new high-speed solution for inter city travel, beating planes and high speed rail for travel time. Various groups have sprung up around the world to propose potential routes and develop the technology. Virgin Hyperloop are one of the companies at the forefront, being the first to run a pod on their test track with live human passengers, reaching speeds of 100 mph over a short 500 meter run.

It’s an exciting technology with a futuristic bent, but to hit the big time, it needs to beat out all comers on price and practicality. Let’s take a look at how it breaks down.

The Mostly Forgotten Story Of Atmospheric Railway

It doesn’t matter whether you know it as a railway, a railroad, a chemin de fer, or a 铁路, it’s a fair certainty that the trains near where you live are most likely to be powered either by diesel or electric locomotives. Over the years from the first horse-drawn tramways to the present day there haven’t been many other ways to power a train, and since steam locomotives are largely the preserve of museums in the 21st century, those two remain as the only two games in town.

But step back to the dawn of the railway age, and it was an entirely different matter. Think of those early-19th-century railway engineer-barons as the Elon Musks and Jeff Bezos’ of their day, and instead of space and hyperloop startups their playground was rail transport. Just as some wild and crazy ideas are spoken about in the world of tech startups today, so it was with the early railways. One of the best-known of these even made it to some real railways, I’m speaking of course about the atmospheric railway.

These trains were propelled not by a locomotive, but by air pressure pushing against a piston in a partially evacuated tube between the tracks.

Continue reading “The Mostly Forgotten Story Of Atmospheric Railway”

Considering The Originality Question

Many Hackaday readers have an interest in older technologies, and from antique motorcycles to tube radios to retrocomputers, you own, conserve and restore them. Sometimes you do so using new parts because the originals are either unavailable or downright awful, but as you do so are you really restoring the item or creating a composite fake without the soul of the original? It’s a question the railway film and documentary maker [Chris Eden-Green] considers with respect to steam locomotives, and as a topic for debate we think it has an interest to a much wider community concerned with older tech.

Along the way the film serves as a fascinating insight for the non railway cognoscenti into the overhaul schedule for a working steam locomotive, for which the mainline railways had huge workshops but which presents a much more significant challenge to a small preserved railway. We wrote a year or two ago about the world’s first preserved railway, the Welsh Tal-y-Llyn narrow gauge line, and as an example the surprise in the video below is just how little original metal was left in its two earliest locomotives after their rebuilding in the 1950s.

The film should provoke some thought and debate among rail enthusiasts, and no doubt among Hackaday readers too. We’re inclined to agree with his conclusion that the machines were made to run rather than gather dust in a museum, and there is no harm in a majorly-restored or even replica locomotive. After all, just as a retrocomputer is as much distinguished by the software it runs, riding a steam train is far more a case of sights and smells than it is of knowing exactly which metal makes up the locomotive.