[James], aka [Turbo Conquering Mega Eagle], is not your typical Hackaday poster boy. Most of his builds have a “Junkyard Wars” vibe, and he’d clearly be a good man to have around in a zombie apocalypse. Especially if the undead start driving tanks around, for which purpose his current anti-tank compound crossbow is apparently being developed.

At its present prototype phase, [James]’ weapon o’ doom looks more fearsome than it actually is. But that’s OK — we’re all about iterative development here. Using leaf springs from a Toyota Hi-Lux truck, this crossbow can store a lot of energy, which is amplified by ludicrously large aluminum cams. [James] put a lot of effort into designing a stock that can deal with these forces, ending up with a composite design of laminated wood and metal. He put a lot of care into the trigger mechanism too, and the receiver sports not only a custom pistol grip cast from aluminum from his fire extinguisher foundry, but a hand-made Picatinny rail for mounting optics. Test shots near the end of the video below give a hint at the power this fully armed and operational crossbow will eventually have. The goal is to disable a running car by penetrating the engine block, and we’re looking forward to that snuff film.

If rubber band-powered crossbows are more your speed, take you pick — fully automatic, 3D-printed, or human-launching.

Continue reading “Junkyard Crossbow Aims To Be A Car Killer”

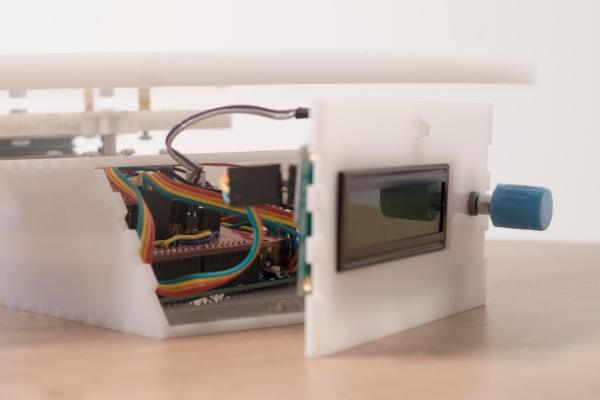

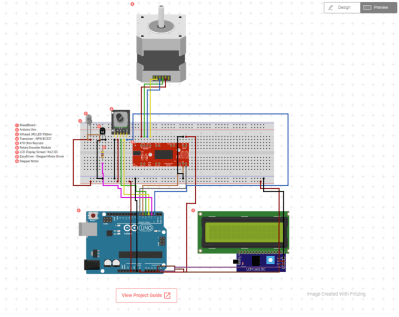

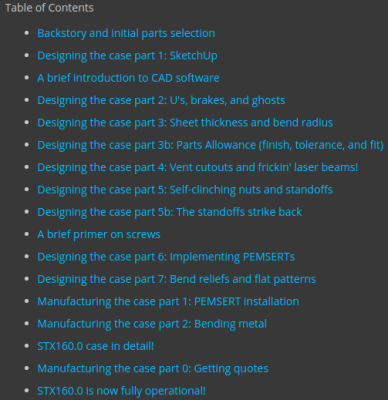

The two really interesting take away’s for us in this project are his meticulous research to find specific parts that met his requirements from among the vast number of available choices. The second is his extremely detailed notes on designing the custom enclosure for this project and make it DFM (design for manufacturing) friendly so it could be mass-produced – just take a look at his “

The two really interesting take away’s for us in this project are his meticulous research to find specific parts that met his requirements from among the vast number of available choices. The second is his extremely detailed notes on designing the custom enclosure for this project and make it DFM (design for manufacturing) friendly so it could be mass-produced – just take a look at his “