The biggest Internet provider in Portugal needed a system to turn FM broadcast stations in Angola, Cabo Verde, and Mozambique into a web stream. Like every good project, the people in charge of the engineering turned to Hackaday staples – Raspberry Pis, Arduinos, and TP-Link routers, all stuffed into an awesome modular rackmount cabinet

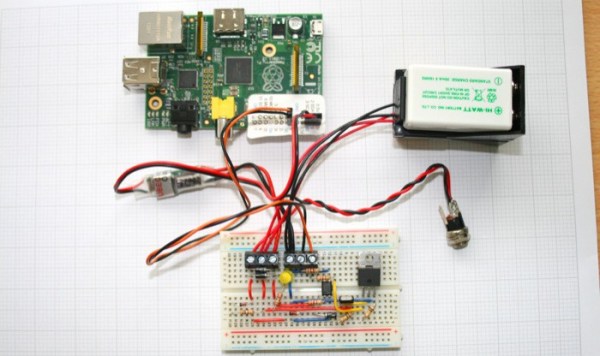

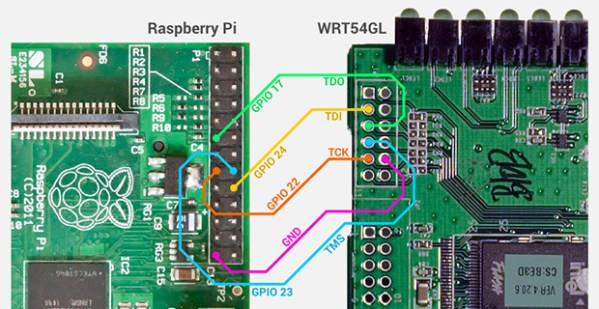

Each module in this gigantic rackmount system includes an Arduino, a Raspberry Pi, a Silicon Labs Si4705 FM receiver chip, and a TI USB audio capture chip that allows the Pi to turn the audio out from the radio receiver into an audio stream. All the Pis are connected to a 24 port Ethernet switch and to a separate master Raspi that converts data received from each module into an icecast stream.

The engineering behind each module is pretty impressive – they’re all hot swappable, have remote shutdown capability, and have voltage divider on the backplane to detect where in the rack it’s placed. It’s a very cool piece of engineering and a very cool example of using off-the-shelf hardware to do something that could be much, much harder.