One of the core features of the scientific community is the concept of “peer review” where any claims made by a scientist are open to be analyzed and reproduced by others in the community for independent verification. This leads to either rejection of ideas which can’t be reproduced, or strengthening of those ideas when they are. In this community we typically only feature the first step of this process, the original projects from various builders, but we don’t often see someone taking those instructions and “peer reviewing” someone’s build. This is one of those rare cases.

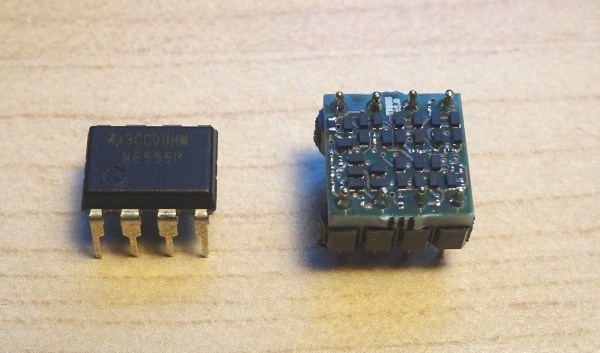

[oxullo] came across [Leo]’s original build for the ultimate continuity tester. This design is much more sensitive than the function which is built in to most multi-meters, and when building this tool specifically some other refinements can be built in as well. [oxullo] began by starting with the original designs, but made several small modifications. Most of these were changing to surface-mount parts, and switching some components for ones already available. Even then, there was still a mistake in the PCB which was eventually corrected. The case for this build is also 3D printed instead of being made out of metal, and with the original video to work from the rest fell into place easily.

[oxullo] is getting comparable results with this continuity tester, so we can officially say that this design is peer reviewed and tested to the highest of standards. If you’re in need of a more sensitive continuity sensor, or just don’t want to shell out for a Fluke meter when you don’t need the rest of its capabilities, this is the way to go. And don’t forget to check out our original write-up for this tester if you missed it the first time around.