We think of the Internet extending to small devices as a modern trend, but it actually is a good example of how everything makes a circle. Today, we want the network to connect to our thermostat and our toaster. But somewhere between the year 1990 and the year 2010, there was a push to make the Internet accessible to the majority of people who didn’t own a computer. The prototypical device, in our mind, was Microsoft’s ill-fated WebTV, but a recent video from [This Does Not Compute] reminded us of another entry in that race: The Audrey from 3COM. Check out the video, below.

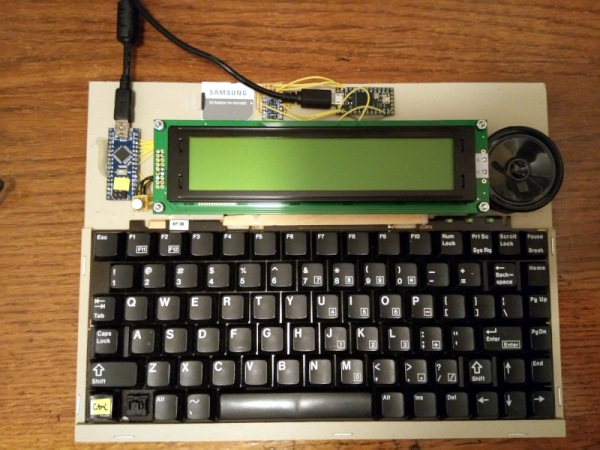

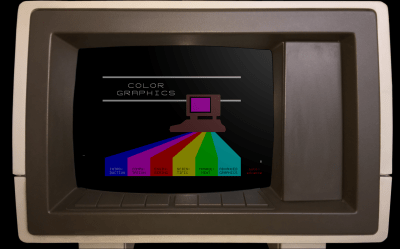

Many devices, like the WebTV, wanted to take over your TV set to save on a display. That doesn’t sound bad today, but you have to remember, the typical TV set in those days was not the high-resolution digital monster you have today, so the experience of surfing the Web on one was suboptimal. The Audrey actually had a cute little screen and a compact keyboard.

Continue reading “The Internet Without The Computer: 1990s Style”