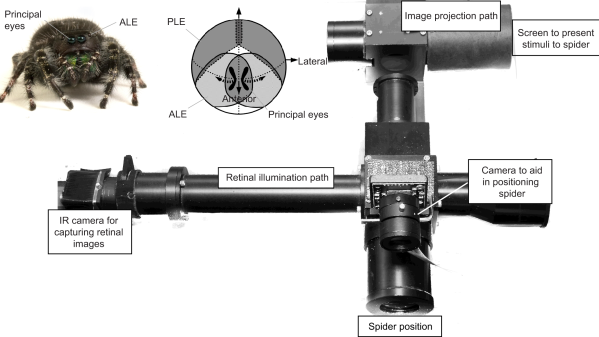

The eyes are windows into the mind, and this research into what jumping spiders look at and why required a clever device that performs eye tracking, but for jumping spiders. The eyesight of these fascinating creatures in some ways has a lot in common with humans. We both perceive a wide-angle region of lower visual fidelity, but are capable of directing our attention to areas of interest within that to see greater detail. Researchers have been able to perform eye-tracking on jumping spiders, literally showing exactly where they are looking in real-time, with the help of a custom device that works a little bit like a miniature movie theatre.

To do this, researchers had to get clever. The unblinking lenses of a spider’s two front-facing primary eyes do not move. Instead, to look at different things, the cone-shaped inside of the eye is shifted around by muscles. This effectively pulls the retina around to point towards different areas of interest. Spiders, whose primary eyes have boomerang-shaped retinas, have an X-shaped region of higher-resolution vision that the spider directs as needed.

So how does the spider eye tracker work? The spider perches on a tiny foam ball and is attached — the help of a harmless and temporary adhesive based on beeswax — to a small bristle. In this way, the spider is held stably in front of a video screen without otherwise being restrained. The spider is shown home movies while an IR camera picks up the reflection of IR off the retinas inside the spider’s two primary eyes. By superimposing the IR reflection onto the displayed video, it becomes possible to literally see exactly where the spider is looking at any given moment. This is similar in some ways to how eye tracking is done for humans, which also uses IR, but watches the position of the pupil.

In the short video embedded below, if you look closely you can see the two retinas make an X-shape of a faintly lighter color than the rest of the background. Watch the spider find and focus on the silhouette of a tasty cricket, but when a dark oval appears and grows larger (as it would look if it were getting closer) the spider’s gaze quickly snaps over to the potential threat.

Feel a need to know more about jumping spiders? This eye-tracking research was featured as part of a larger Science News article highlighting the deep sensory spectrum these fascinating creatures inhabit, most of which is completely inaccessible to humans.

Continue reading “Eye-Tracking Device Is A Tiny Movie Theatre For Jumping Spiders”