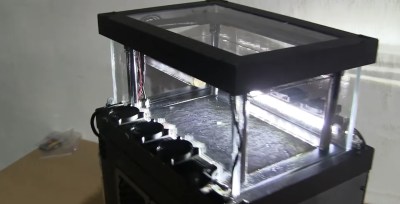

Cloud chambers are an exciting and highly visual science experiment. They’re fascinating to watch as you can see the passage of subatomic particles from radioactive decay with your very own eyes. Many elect to build small chambers based on thermoelectric Peltier elements, but [Cloudylabs] decided to do something on a grander scale.

[Cloudylabs] started building cloud chambers after first seeing one in a museum back in 2010. The first prototype was an air-cooled Peltier device, with a cooled area of just 4x4cm. Over the years, and after building many more Peltier-based chambers, it became apparent that the thermoelectric modules were somewhat less than robust, often failing after many thermal cycles. Wanting to take things up a notch, [Cloudylabs] elected to build a much larger unit based on phase-change technology, akin to the way a refrigerator works.

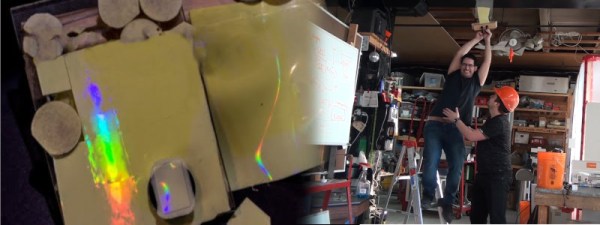

The final product is astounding, consisting of a 32x18cm actively cooled area mounted within a large glass viewing case. A magnet is mounted underneath which causes certain particles to curve in relation to the field, as well as an electrically charged grid up top. The chamber is capable of operating for up to 12 hours without requiring any user intervention.

Cloud chambers are always beautiful, and even moreso at this larger scale. When radioactive materials are introduced into the chamber the trails generated are long and easily visible. It’s a daunting build however, and the final product weighs over 30 kilograms. You might want to start with something a little smaller for your first build. Video after the break.