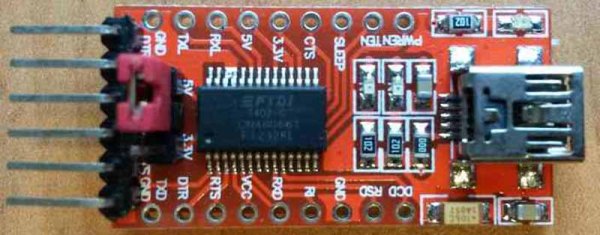

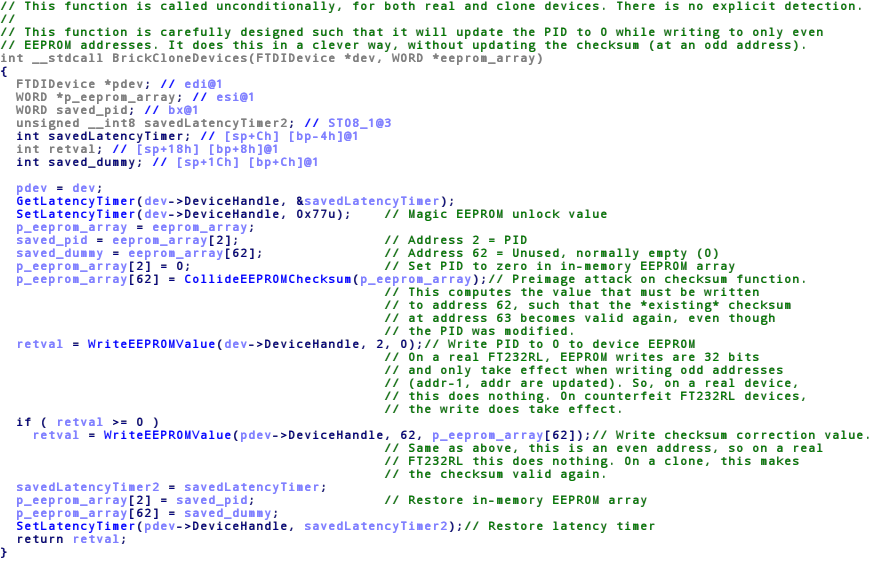

When it comes to electronic hobbyists and EEs, there is no company that deserves a few raised eyebrows than FTDI. They made their name with USB converter chips, namely USB to serial chips that are still very popular today. So popular, in fact, that clones of these chips are frequently found in the $2 Arduinos from China, and other very low-cost devices. A little more than a year ago, a few clever people noticed FTDI drivers were bricking these counterfeit chips by setting the USB PID to 0000. The Internet reacted to this move and FTDI quickly backed down from that position. The Windows driver was fixed, for about a year until the same shenanigans were found again.

Adafruit recently sat down with [Fred Dart], CEO of FTDI, giving us all the first facts and figures that aren’t from people frustrated with Windows’ automatically updated drivers. The most interesting information from [Fred Dart] is how FTDI first found these counterfeit chips, what FTDI chips are being counterfeited, and how many different companies are copying these chips.

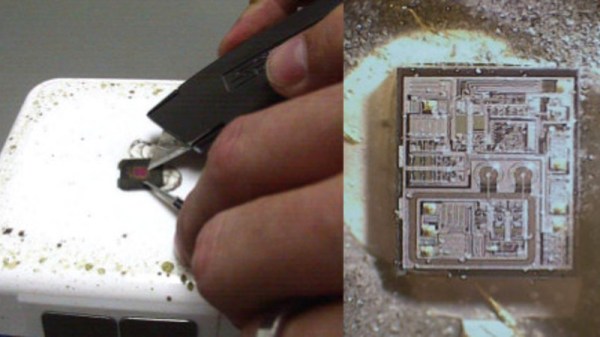

The company first realized they were being cloned when they couldn’t reproduce results of a Chinese-made ‘FTDI’ USB to RS232 cable that behaved strangely. A sample of the cables were shipped to FTDI and after inspecting the chip inside, FTDI found it was a clone with a significantly different architecture than a genuine chip.

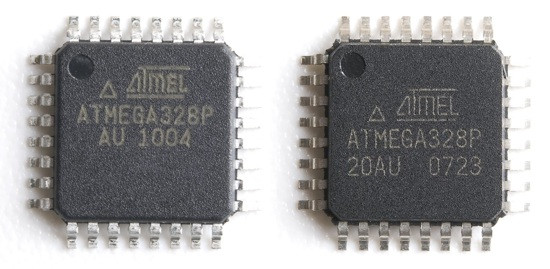

So far, the counterfeiters appear to only be counterfeiting the SSOP version of the FT232RL and occasionally the older FT232BL chip. From what FTDI has seen, there appears to be only one or two companies counterfeiting chips.

As the CEO of FTDI, [Fred] has a few insights into what can be done to stop counterfeiters in China. The most important is to trademark the logo. This isn’t just the logo for a webpage, but one that can be laser etched onto the plastic package of the chip. US Customs has been very amenable to identifying counterfeit components, and this has led to several shipments being destroyed. Legal action, however, is a bit hard in China, and FTDI is dealing with a gang that counterfeits more than FTDI chips; there’s a high likelihood this gang was responsible for the fake Prolific PL23o3 chips a few years ago.

As far as FTDI bricking counterfeit chips is concerned, [Fred Dart] wasn’t silent on the issue, he merely wasn’t asked the question and didn’t bring it up himself.