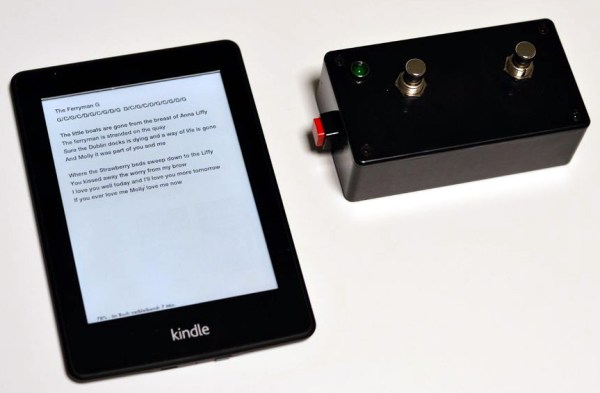

While we tend to think of Amazon’s e-paper Kindles as more or less single-purpose devices (which to be fair, is how they’re advertised), there’s actually a full-featured Linux computer running behind that simple interface, just waiting to be put to work. Given how cheap you can get old Kindles on the second hand market, this has always struck us as something of a wasted opportunity.

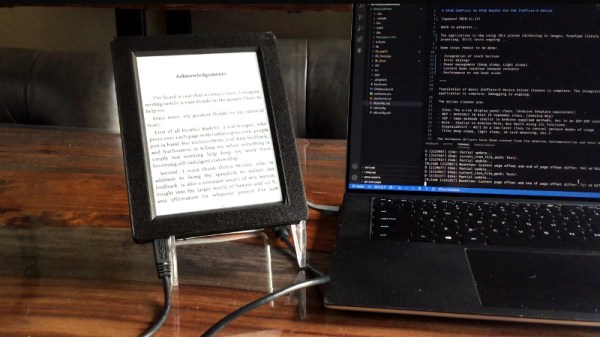

This is why we love to see projects like Kindlefusion from [Diggedypomme]. It turns the Kindle into a picture frame to show off the latest in machine learning art thanks to Stable Diffusion. Just connect your browser to the web-based control interface running on the Kindle, give it a prompt, and away it goes. There are also functions to recall previously generated images, and if you’re connecting from a mobile device, support for creating images from voice prompts.

All you need is a Kindle that can be jailbroken, though technically the software has only been tested against older third and fourth-generation hardware. From there you install a few required packages as listed in the project documentation, including Python 3. Then you just move the Kindlefusion package over either via USB or SSH, and do a little final housekeeping before starting it up and letting it take over the Kindle’s normal UI.

Given the somewhat niche nature of Kindle hacking, we’re particularly glad to see that [Diggedypomme] went through the trouble of explaining the nuances of getting the e-reader ready to run your own code. While it’s not difficult to do, there are plenty of pitfalls if you’ve never done it before, so a concise guide is a nice thing to have. Unfortunately, it seems like Amazon has recently gone on the offensive, with firmware updates blocking the exploits the community was using for jailbreaking on all but the older models that are no longer officially supported.

While it’s a shame you can’t just pick up a new Kindle and start hacking (at least, for now), there are still millions of older devices floating around that could be put to good use. Hopefully, projects like this can help inspire others to pick one up and start experimenting with what’s possible.

Continue reading “Turning Old Kindles Into AI Powered Picture Frames”