The range of human hearing goes up to about 20 kilohertz, which is fine for our purposes, but is pretty poor compared to plenty of other animal species. Dogs famously can hear up to about 60 kHz, and dolphins are known to distinguish sounds up to 100 kHz. But for extremely high frequencies we’ll want to take a step into the world of bats. Some use echolocation to locate each other and their food sources, and bats like the pipistrelle can listen in to sounds up to 350 kHz. To listen to them you’ll need a device like the π*pistrelle. (Ed Note: a better explanation is available at the project’s website.)

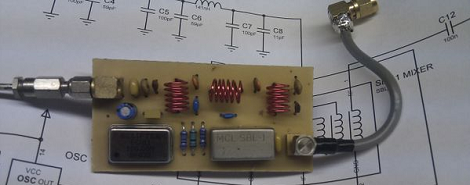

The original implementation of the bat detector was based on a Raspberry Pi Pico, from which it gets its name. But there have been several improvements on it in the years since it was first developed. The latest can detect bats when it hears their 350 kHz sonar calls thanks to an ultrasonic microphone and op amp. The device then records the bat sounds and then either heterodynes the sound down or time-expands it to human-audible range so the calls can actually be heard. There’s an LED display on the board as well as three input buttons, but an iOS companion app is available to interact with the device as well.

If you want to know for sure which species is flying around at night, you can use machine learning to help figure that out.