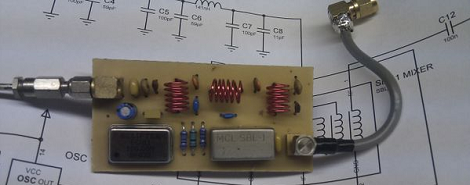

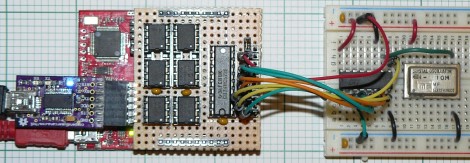

Here’s a 6-channel logic analyzer shield for the MSP430 Launchpad. It manages an eyebrow-raising 16 million samples per second. The prototype seen above is made on a hunk of protoboard with point-to-point soldering. [oPossum] did lay out a PCB — which is just 50mmx50mm — but has not had any produced quite yet.

He calls it the LogicBoost, and based it on the the LogicShrimp design. The sextuplet of 8-pin chips are all SPI RAM. These are responsible for storing the samples, with a 74HC573 latch routing the traffic. The MSP430 chip provides the SPI clock, and the Launchpad’s virtual com port can be used to push the data to a computer for graphing. That’s a bit slow so [oPossum] also included an optional header for an FTDI board that will do a faster job. The sample rate can be adjusted by tweaking the internal oscillator setting of the chip; there’s plenty to choose from so it will work for just about any purpose (as long as you don’t surpass the 16 Msps speed limit).

[via Dangerous Prototypes]