For how many can be found on the workbenches and in the toolboxes of makers and hackers the world over, finding a glue gun that does more than just heat up and drip glue everywhere can be a challenge. [Ben Heck] finally solved this problem with a hot glue gun that’s more like an extruder from a 3D printer than a piece of junk you can pick up at Walmart for a few dollars.

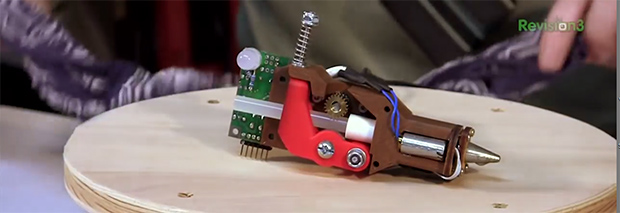

By far, the most difficult part of this project was the glue stick extruder. For this, [Ben] used a DC motor with a two-stage planetary gear system. This drives a homemade hobbed bolt, just like the extruder in 99% of 3D printers. The glue stick is wedged up against the hobbed bolt with a few 3D printed parts and a spring making for a very compact glue stick extruder.

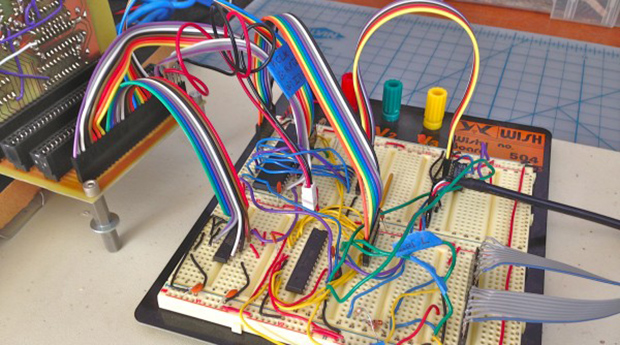

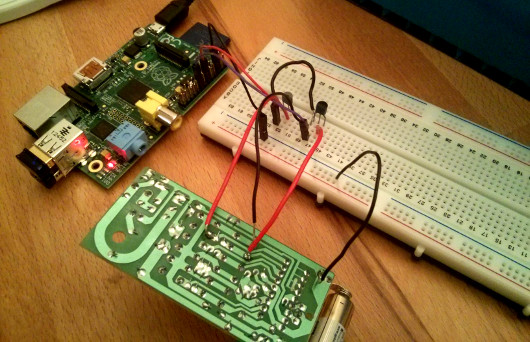

The electronics are a small AVR board [Ben] made for a previous episode, a thermistor attached to the hot end of the glue gun, a solid state relay for the heater, and analog controls for speed and temperature settings. After finishing the mechanics and electronics, [Ben] took everything apart and put it back together in a glue gun-shaped object.

The finished product is actually pretty nice. It lays down constistant beads of hot glue and thanks to a little bit of motor retraction won’t drip.

You can check out both parts of [Ben]’s build below.