[Gene] has a project that writes a lot of settings to a PIC microcontroller’s Flash memory. Flash has limited read/erase cycles, and although the obvious problem can be mitigated with error correction codes, it’s a good idea to figure out how Flash fails before picking a certain ECC. This now became a problem of banging on PICs until they puked, and mapping out the failure pattern of the Flash memory in these chips.

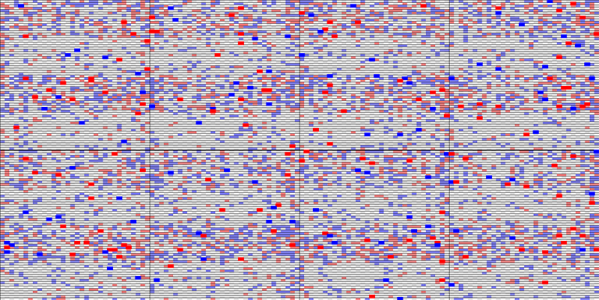

The chip on the chopping block for this experiment was a PIC32MX150, with 128K of NOR Flash and 3K of extra Flash for a bootloader. There’s hardware support for erasing all the Flash, erasing one page, programming one row, and programming one word. Because [Gene] expected one bit to work after it had failed and vice versa, the testing protocol used RAM buffers to compare the last state and new state for each bit tested in the Flash. 2K of RAM was tested at a time, with a total of 16K of Flash testable. The code basically cycles through a loop that erases all the pages (should set all bits to ‘1’), read the pages to check if all bits were ‘1’, writes ‘0’ to all pages, and reads pages to check if all bits were ‘0’. The output of the test was a 4.6 GB text file that looked something like this:

Continue reading “Flash Memory Endurance Testing”