A few months ago, [Matt] realized he needed another battery for his Thinkpad X230T. The original battery would barely last 10 minutes, and he wanted a battery that would last an entire plane flight. When his new battery arrived, he installed it only to find a disturbing message displayed during startup: “The system does not support batteries that are not genuine Lenovo-made or authorized.” The battery was chipped, and now [Matt] had to figure out a way around this.

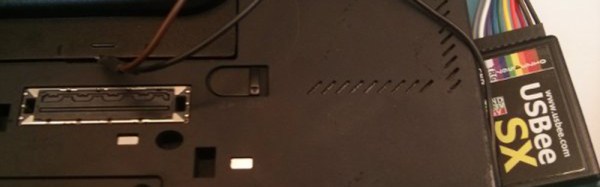

Most recent laptop batteries have an integrated controller that implements the Smart Battery Specification (SBS) over the SMBus, an I2C-like protocol with data and clock pins right on the battery connector. After connecting a USBee logic analyser to the relevant pins, [Matt] found the battery didn’t report itself correctly to the Thinkpad’s battery controller.

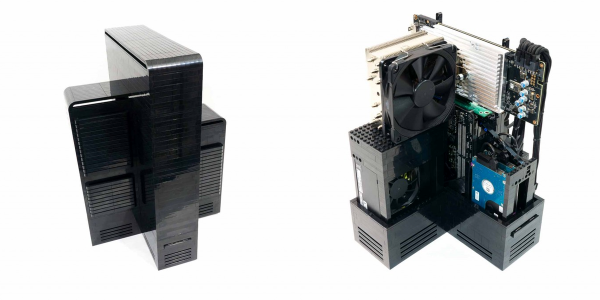

With the problem clearly defined, [Matt] had a few options open to him. The first was opening both batteries, and replacing the cells in the old (genuine) battery with the cells in the newer (not genuine) battery. If you’ve ever taken apart a laptop battery, you’ll know this is the worst choice. There are fiddly bits of plastic and glue, and if you’re lucky enough to get the battery apart in a reasonably clean matter, you’re not going to get it back together again. The second option was modifying the firmware on the non-genuine battery. [Charlie Miller] has done a bit of research on this, but none of the standard SBS commands would work on the non-genuine battery, meaning [Matt] would need to take the battery apart to see what’s inside. The third option is an embedded controller that taps into the SMBus on the charger connector, but according to [Matt], adding extra electronics to a laptop isn’t ideal. The last option is modifying the Thinkpad’s embedded controller firmware. This last option is the one he went with.

There’s an exceptionally large community dedicated to Thinkpad firmware hacks, reverse engineering, and generally turning Thinkpads into the best machines they can be. With the schematics for his laptop in hand, [Matt] found the embedded controller responsible for battery charging, and after taking a few educated guesses had some success. He ran into problems, though, when he discovered some strangely encrypted code in the software image. A few Russian developers had run into the same problem, and by wiring up a JTAG to the embedded controller chip, this dev had a fully decrypted Flash image of whatever was on this chip.

[Matt]’s next steps are taking the encrypted image and building new firmware for the embedded controller that will allow him to charge is off-brand, and probably every other battery on the planet. As far as interesting mods go, this is right at the top, soon to be overshadowed by a few dozen comments complaining about DRM in batteries.

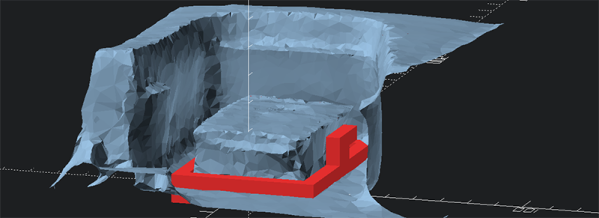

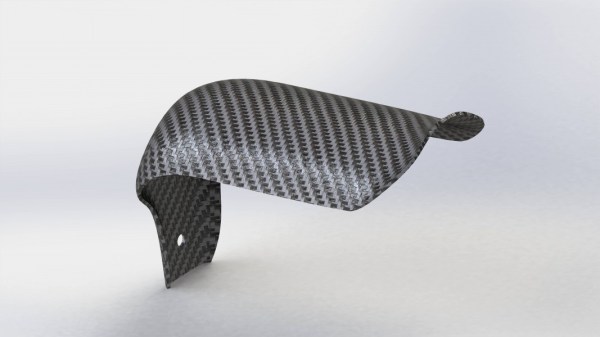

Photogrammetry requires taking a few dozen pictures with a camera, using software to turn these 2D images into a 3D model, and building the new part from that model. The software [Stefan] is using is

Photogrammetry requires taking a few dozen pictures with a camera, using software to turn these 2D images into a 3D model, and building the new part from that model. The software [Stefan] is using is

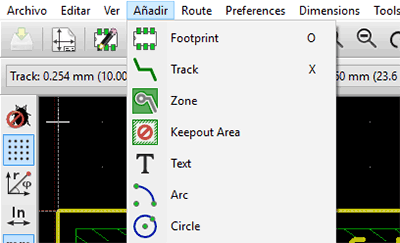

Mientras que ha habido otros intentos por localizar KiCad a otros idiomas, la mayoría de estos proyectos se encuentran incompletos. En una actualización de KiCad hace algunos meses, la localización al español ya contaba con algunas cadenas ya traducidas, pero no demasiadas. Los esfuerzos de [ElektroQuark] han acercado KiCad a millones de hablantes nativos de español, no solo algunos de sus menús.

Mientras que ha habido otros intentos por localizar KiCad a otros idiomas, la mayoría de estos proyectos se encuentran incompletos. En una actualización de KiCad hace algunos meses, la localización al español ya contaba con algunas cadenas ya traducidas, pero no demasiadas. Los esfuerzos de [ElektroQuark] han acercado KiCad a millones de hablantes nativos de español, no solo algunos de sus menús.