Of all the tools that exist, there aren’t many more futuristic than the plasma cutter, if a modern Star Wars cosplay if your idea of futuristic. That being said, plasma cutters are a powerful tool capable of making neat cuts through practically any material, and there are certainly worst ways to play with high voltage.

Lucky enough, [Plasanator] posted their tutorial for how to make a plasma cutter, showing the steps through which they gathered parts from “old microwaves, stoves, water heaters, air conditioners, car parts, and more” in the hopes of creating a low-budget plasma cutter better than any on YouTube or from a commercial vendor.

The plasma cutter does end up working up quite an arc, with the strength to slice through quarter-inch steel “like a hot knife through butter”.

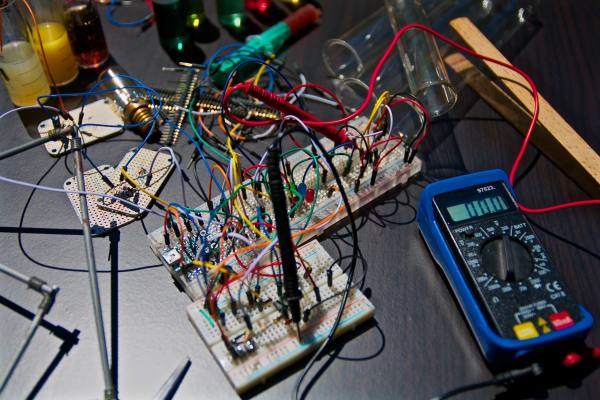

Its parts list and schematic divide the systems into power control, high current DC, low voltage DC, and high voltage arc start:

- The power control contains the step down transformer and contactor (allows the DC components to come on line)

- The high current DC contains the bridge rectifier, large capacitors, and reed switch (used as a current sensor to allow the high voltage arc to fire right when the current starts to travel to the head, shutting down the high voltage arc system when it’s no longer necessary)

- The low voltage DC contains the power switch, auto relays, 12V transformer, 120V terminal blocks, and a terminal strip

- The high voltage arc start contains the microwave capacitor and a car ignition coil

At the cutting end, 13A is used to cut through quarter-inch steel. Considering the considerably high voltage cutter this is, a 20 A line breaker is needed for safety.

Once the project is in a more refined state, [Plasanator] plans on hiding components like the massive capacitors and transformer behind a metal or plastic enclosure, rather than have them exposed. This is mainly for safety reasons, although having the parts exposed is evocative of a steampunk aesthetic.

In several past designs, stove coils were used as current resistors and a Chevy control module as the high voltage arc start. The schematic may have become more refined with each build, but [Plasanator]’s desire to use whatever components were available certainly has not disappeared.

Continue reading “Make Your Own Plasma Cutter” →