Vacuum tubes have been around for ages, and for better or worse, they have their advocates for use in amplifiers and preamps. However, tubes are simply inconvenient devices. Even a 12AX7 preamp tube is huge relative to a handful of transistors, tubes require weird voltages, and each and every one of them is a through-hole device that doesn’t lend itself to machine assembly.

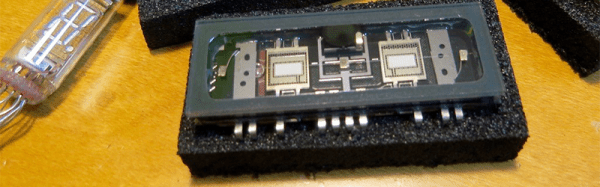

This changed recently with the introduction a strange new tube from Japan. Noritake and Korg recently introduced a triode that uses the same packaging as VFD displays. The Korg Nutube is a vacuum tube that operates at lower voltages, is smaller than the usual preamp tubes, and still has the vacuum tube sound.

For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Kodera] is building a headphone amp with this new tube. Is a tube-based headphone amp particularly novel? No. But this is the first we’ve seen anyone playing around with this new, interesting piece of technology.

The requirements for this Nutube are simple enough, and the minimum anode voltage of this tube is just 8 V. [Kodera]’s circuit is running the tube at 12 V, and the only other circuitry in this preamp are a few coupling caps and an op-amp just before the power stage.

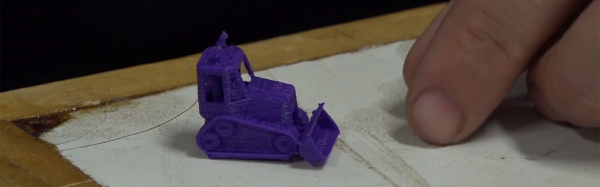

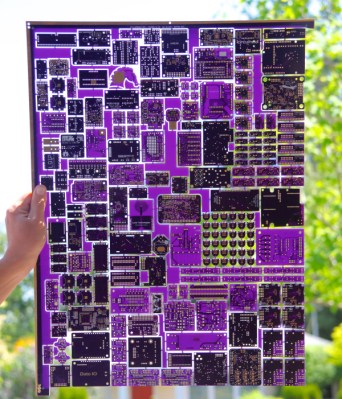

[Kodera] has crammed this circuit into a proper amplifier using a 2 x 15 W class-D chip from TI. It’s really a phenomenally simple circuit that’s also remarkably tiny. These kits are actually available on Tindie. Time will tell if the Nutube is picked up by some big-time manufacturers, but we’re happy to see someone is playing around with the latest advances in tube amp technology.