If you don’t have a niece or nephew we encourage you to get one because they provide a great excuse to take apart kids’ toys.

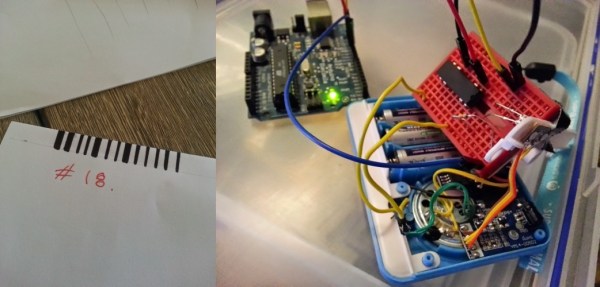

[Sam] had just bought some animal-themed trading cards. These particular cards accompany a card-reader that uses barcodes to play some audio specific to each animal when swiped. So [Sam] convinces her niece that they should draw their own bar codes. Of course it’s not that easy: the barcodes end up having even and odd parity bits tacked on to verify a valid read. But after some solid reasoning plus trial-and-error, [Sam] convinces her niece that the world runs on science rather than magic.

But it can’t end there; [Sam] wants to hear all the animals. Printing out a bunch of cards is tedious, so [Sam] opens up the card reader and programs and Arduino to press a button and blink an IR LED to simulate a card swipe. (Kudos!) Now she can easily go through all 1023 possible values for the animal cards and play all the audio tracks, and her niece gets to hear more animal sounds than any child could desire.

Along the way, [Sam] found some interesting non-animal sounds that she thinks are Easter eggs but we would wager are for future use in a contest or promotional drawing or something similar. Either way, its great fun to get to listen in on more than you’re supposed to. And what better way to educate the next generation of little hackers than by spending some quality time together spoofing bar codes with pen and paper?