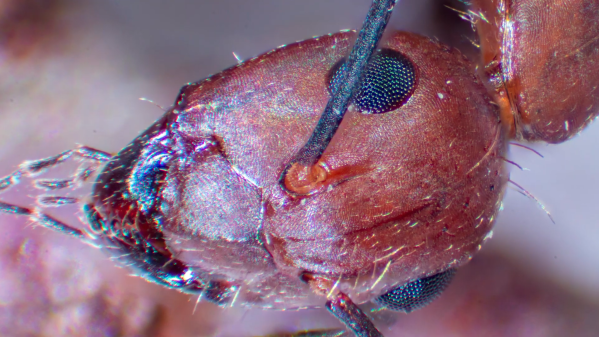

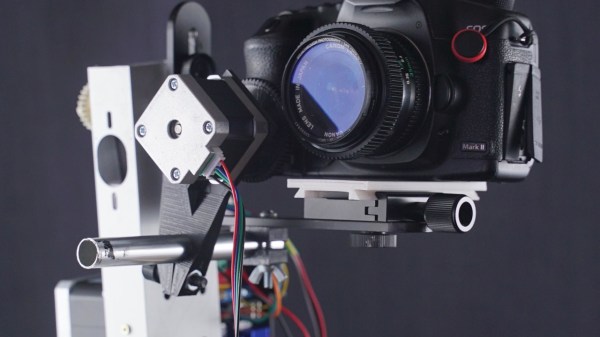

When taking pictures of the night sky, any noise picked up by the sensor can obscure the desired result. One major cause of noise in CMOS sensors is heat—even small amounts can degrade the final image. To combat this, [Francisco C] of Deep SkyLab retrofitted an old Canon T1i DSLR with an external cooler to reduce thermal noise, which introduces random pixel variations that can hide faint stars.

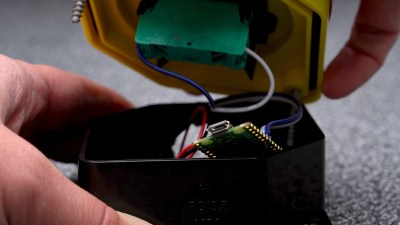

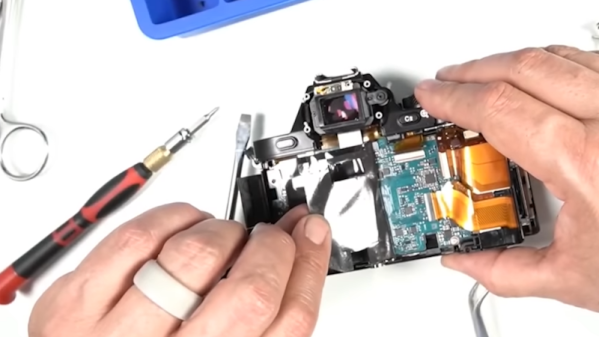

While dedicated astrophotography cameras exist—and [Francisco C] even owns one—he wanted to see if he could improve an old DSLR by actively cooling its image sensor. He began with minor surgery, removing the rear panel and screen to expose the back of the sensor. Using a sub-$20 Peltier cooler (also called a TEC, or Thermoelectric Cooler), he placed its cold side against the sensor, creating a path to draw heat away.

Reassembling the camera required some compromises, such as leaving off the LCD screen due to space constraints. To prevent light leaks, [Francisco C] covered the exposed PCBs and viewfinder with tape. He then tested the setup, taking photos with the TEC disabled and enabled. Without cooling, the sensor started at 67°F but quickly rose to 88°F in sequential shots. With the TEC enabled, the sensor remained steady at 67°F across all shots, yielding a 2.8x improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio. Thanks to [Francisco C] for sharing this project! Check out his project page for more details, and explore our other astrophotography hacks for inspiration.

Continue reading “Cold Sensor, Hot Results: Upgrading A DSLR For Astrophotography”