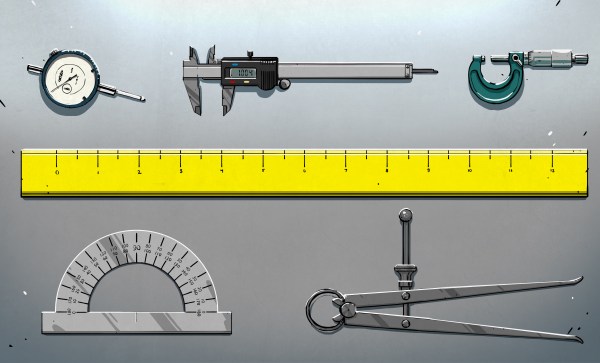

I really enjoyed reading Anne Ogborn’s piece on making simple DIY measurement devices for physical quantities like force, power, and torque. It is full of food for thought, if you’re building something small with motors and need to figure out how to spec them out.

Aside from a few good examples, what I really took home from this piece is how easy it can be to take approximate measurements. Take the push stick, which is a spring-loaded plunger in a transparent barrel. You use it to measure force by, well, squeezing the spring and reading off how far it deflects. That’s obvious, but the real trick is in calibration by pushing it into a weighing scale and marking divisions on the barrel. That quickly and easily turns “it’s pressing this hard” into an actual numerical force measurement.

The accuracy and precision of the push stick are limited by the quality of your scale and the fineness of the pen tip that you use to mark the barrel. But when you’re just looking to choose among two servo motors, this kind of seat-of-the-pants measure is more than enough to buy the right part. Almost any actual measurement is better than a wild-ass guess, so don’t hold yourself to outrageous standards or think that improvised quantitative measurement devices aren’t going to get the job done.

Al Williams quoted a teacher of his as saying that the soul of metrology is “taking something you know and using it to find something you don’t know”, and that sums up this piece nicely. But it’s also almost a hacker manifesto: “take something you can do and use it to do something that you can’t (yet)”.

Got any good measurement hacks you’d like to share?