If you think of a medical x-ray, it is likely that you are imagining a photographic plate as its imaging device. Clipped to your tooth by your dentist perhaps, or one of the infamous pictures of the hands of [Thomas Edison]’s assistant [Clarence Madison Dally].

As with the rest of photography, the science of x-ray imaging has benefited from digital technology, and it is now well established that your hospital x-ray is likely to be captured by an electronic imaging device. Indeed these have now been in use for so long that their first generation can even be bought by an experimenter for an affordable sum, and that is what the ever-resourceful [Lucy Fauth] with the assistance of [Jana Marie Hemsing], has done. Their Trophy DigiPan digital x-ray image sensor was theirs for around a hundred Euros, and though it’s outdated in medical terms it still has huge potential for the x-ray experimenter.

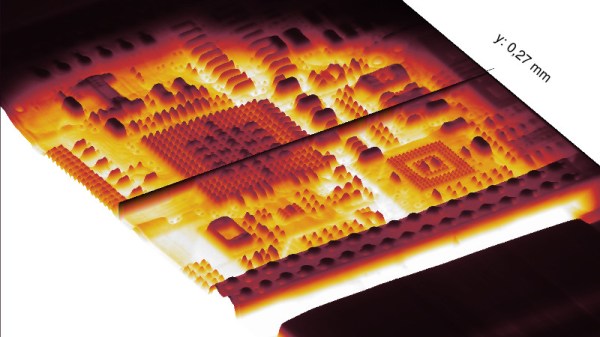

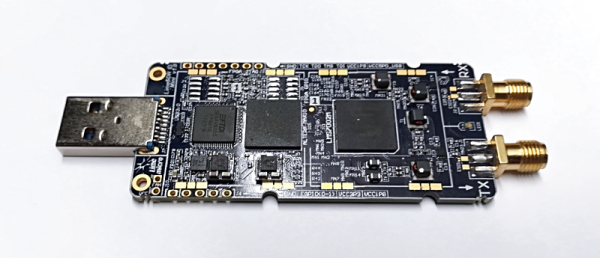

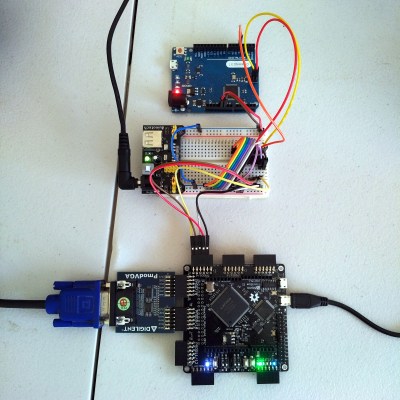

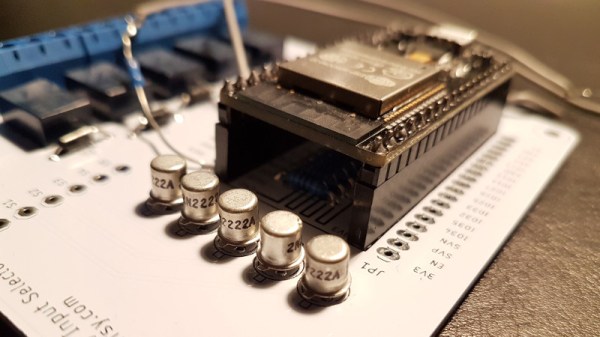

The write-up is a fascinating journey into the mechanics of an x-ray sensor, with the explanation of how earlier devices such as this one are in fact linear CCD sensors which track across the exposed area behind a scintillator layer in a similar fashion to the optical sensor in a flatbed scanner. The interface is revealed as an RS422 serial port, and the device is discovered to be a standalone unit that does not require any commands to start scanning. On power-up it sends a greyscale image, and a bit of Sigrok examination of the non-standard serial stream was able to reveal it as 12-bit data direct from the sensor. From those beginnings they progressed to an FPGA-based data processor and topped it all off with a very tidy power supply in a laser-cut box.

It’s appreciated that x-rays are a particularly hazardous medium to experiment with, and we note from their videos that they are using some form of shielding. The source is a handheld fluoroscope of the type used in sports medicine that produces a narrow beam. If you remember the discovery of an unexpected GameBoy you will be aware that medical electronics seems to be something of a speciality in those quarters, as do autonomous box carriers.