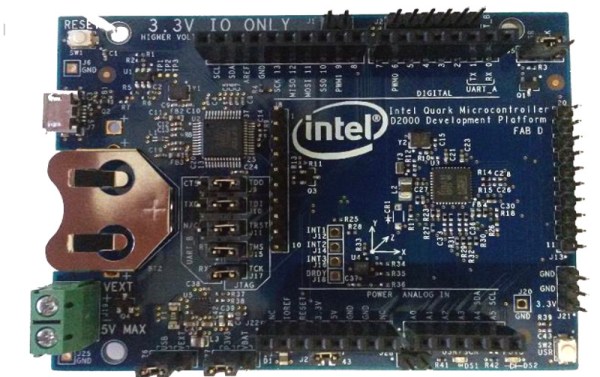

Intel have a developer board that is new to the market, based on their Quark (formerly “Mint Valley”) D2000 low-power x86 microcontroller. This is a micropower 32-bit processor running at 32MHz, and with 32kB of Flash and 8kB of RAM. It’s roughly equivalent to a Pentium-class processor without the x87 FPU, and it has the usual impressive array of built-in microcontroller peripherals and I/O choices.

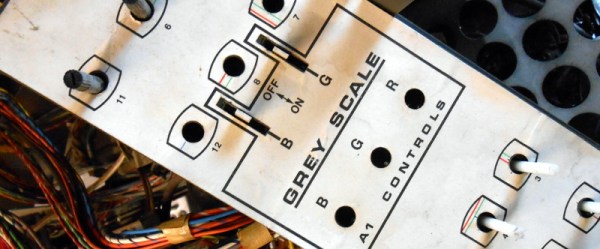

The board has an Arduino-compatible shield footprint, an FTDI chip for USB connectivity, a compass, acceleration, and temperature sensor chip, and a coin cell holder with micropower switching regulator. Intel provide their own System Studio For Microcontrollers dev environment, based around the familiar Eclipse IDE.

Best of all is the price, under $15 from an assortment of the usual large electronics wholesalers.

This board joins a throng of others in the low-cost microcontroller development board space, each of which will have attributes that its manufacturers will hope make it stand out. Facing such competition the Intel board will have to be something rather special to achieve that aim, so why should it excite your interest? We would point to the low price, the x86 code if that is your flavour of choice, and the relatively tiny power consumption.

Stepping back from the dev board for a moment, consider this processor as an illustration of technological progress in semiconductor fabrication. Over twenty years ago this chip’s Pentium ancestor ran on 5 volts and got so hot you could fry an egg on it, here is a Pentium that can run on a few milliwatts from a coin cell. Fortunately you won’t be running Windows 95 on it though.

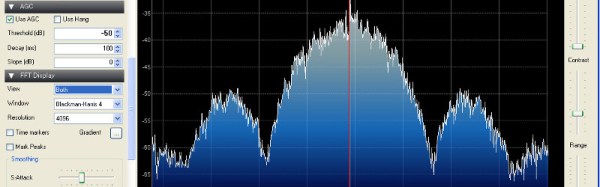

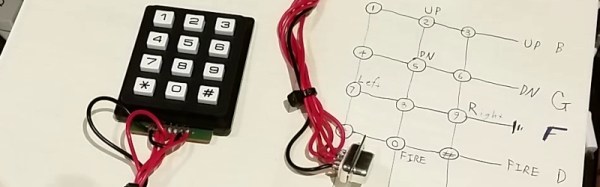

We’re sure we’ll see plenty of projects here in the future using the Quark. Intel’s previous effort in this space, the Edison, has made several appearances. We’ve covered its launch in 2014, looked at someone running Doom on it, and examined its use with audio effects.

Thanks [Nolan M] for the tip.