If you are a lover of the aesthetic of vintage photography and Instagram’s filters don’t quite cut it for you, then there are plenty of opportunities even in this post-film age to sample the real thing. Plastic lens cameras from the former Soviet Bloc countries or the Pacific rim are still in production, and you can still buy 35mm and 120 roll film to put in them.

You can even still buy 8mm film for your vintage movie camera, but it’s rather pricey. [Claire Wright] is a young film maker who had an old 8mm camera and really wanted that analog film feel to her work, and she and her father solved this problem by using the 8mm camera’s lens in front of a Raspberry Pi camera sensor. Since an 8mm film frame is 4.5mm x 3.3mm and the Pi camera sensor size is 3.76mm x 2.74mm, it’s quite a good fit.

Their first prototype had a custom case which concealed the Pi camera behind the lens on rails taken from an old CD-ROM drive, and had an HDMI screen on top and a pistol grip to make it portable. An external thumb screw allowed the camera to be positioned in the focal plane.

A further refinement has stepper motor driven focus driven from an Adafruit motor drive HAT. The software is simply the standard Pi camera utilities. To demonstrate the system, she made a short video about how it came to be, and took the camera on a road trip to Austin, Texas. She tells us a local 3D print shop is working on a 3D model to replicate the camera, but sadly as yet there are no resources for the Hackaday crowd to examine.

Continue reading “Vintage 8mm Camera Now Powered By Raspberry Pi”

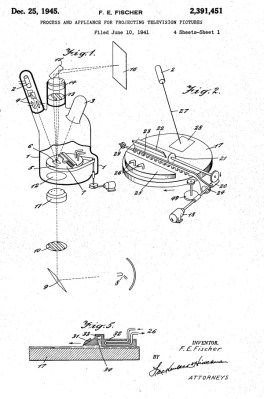

LCD technology was invented in the 1970s, while DLP was invented at the end of the 1980s. So how did the video projectors that were such a staple of televised spectaculars in the preceding decades work? For that matter, how did NASA project their status displays on the huge screen at Mission Control? Certainly not with CRT technology, even the brightest CRT projectors weren’t up to filling a cinema-sized screen.

LCD technology was invented in the 1970s, while DLP was invented at the end of the 1980s. So how did the video projectors that were such a staple of televised spectaculars in the preceding decades work? For that matter, how did NASA project their status displays on the huge screen at Mission Control? Certainly not with CRT technology, even the brightest CRT projectors weren’t up to filling a cinema-sized screen.