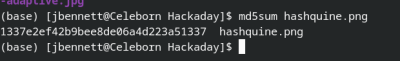

A hashquine is a fun way to show off your crypto-tricks — It’s a file that contains its own hash. In some file types it’s trivial, you just pick the hash to hit, and then put random data in a comment or other invisible field till you get a collision. A Python script that prints its own hash would be easy. But not every file type is so easy. Take PNG for instance. these files are split into chunks of data, and each chunk is both CRC-32 and adler32 checksummed. Make one change, and everything changes, in three places at once. Good luck finding that collision. So how exactly did [David Buchanan] generate that beautiful PNG, which does in fact md5sum to the value in the image? Very cleverly.

Thankfully [David] shared some of his tricks, and they’re pretty neat. The technique he details is a meet-in-the-middle hack, where 36 pairs of MD5 collision blocks are found, with the understanding that these 36 blocks will get added to the file. For each block, either A or B of the pair will get plugged in at that location, and the md5sum won’t change. It’s a total of 2^36 possible combinations of these blocks, which is more computation than was practical for this particular hack. The solution is to pre-compute the results of every possible combination of the first 18 blocks, and store the results in a lookup table. The second half of the collisions are run backwards from a target CRC value, and the result checked against the lookup table. Find a hit, and you just found a series of blocks that matches both your target md5sum and CRC32 results.

Thankfully [David] shared some of his tricks, and they’re pretty neat. The technique he details is a meet-in-the-middle hack, where 36 pairs of MD5 collision blocks are found, with the understanding that these 36 blocks will get added to the file. For each block, either A or B of the pair will get plugged in at that location, and the md5sum won’t change. It’s a total of 2^36 possible combinations of these blocks, which is more computation than was practical for this particular hack. The solution is to pre-compute the results of every possible combination of the first 18 blocks, and store the results in a lookup table. The second half of the collisions are run backwards from a target CRC value, and the result checked against the lookup table. Find a hit, and you just found a series of blocks that matches both your target md5sum and CRC32 results.

Thanks to [Julian] for the tip! And as he described it, this hack is one that gets more impressive the more you think about it. Enjoy!