The last time [Mark] was at the scrap yard, he managed to find the analogue input and output cards of an old Akai DR8 studio hard drive recorder. These cards offered great possibilities (8 ADC inputs, 12 DAC outputs) so he repaired them and made a whole audio system out of them.

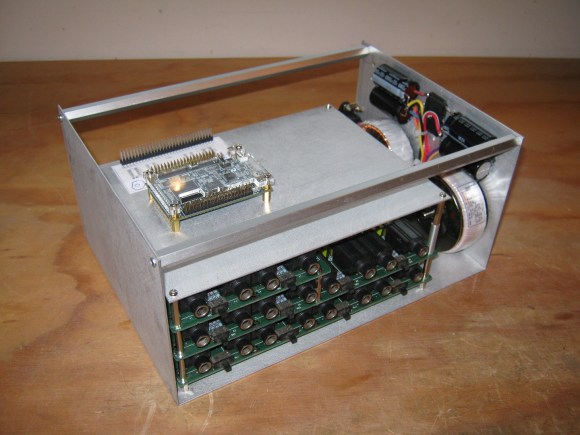

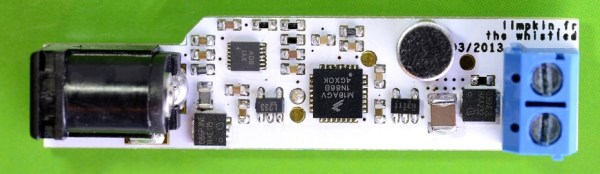

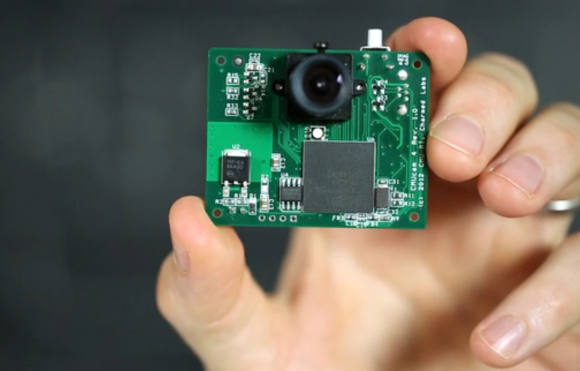

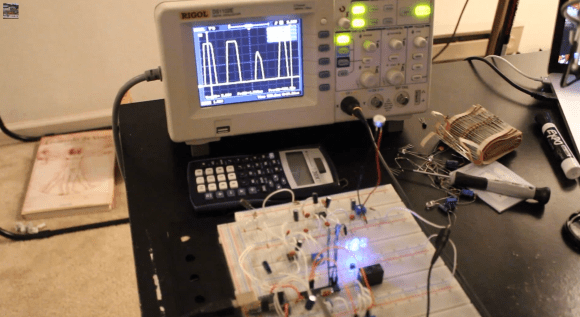

The repair only involved changing a couple of low dropout regulators. Afterwards, [Mark] interfaced one of his CPLD development boards so he could produce some sine waves and digitize signals generated from a PC based audio test unit. He then made the frame shown in the picture above and switched to an Altera Cyclone IV FPGA. To complete his system, he designed a small board to attach a VGA screen, and another to use the nRF24L01 wireless module.

Inside the FPGA, [Mark] used a NIOS II soft core processor to orchestrate the complete system and display a nice user interface. He even made another system with an USB host plug to connect MIDI enabled peripherals, allowing him to wirelessly control his creation.