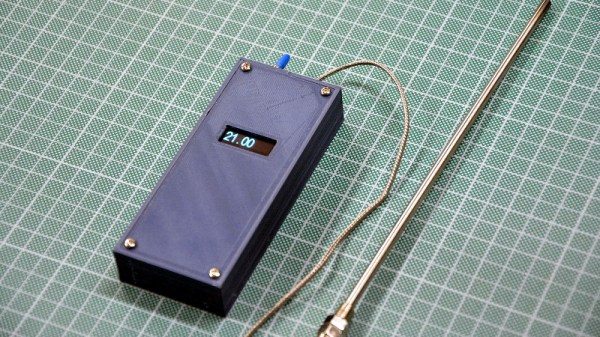

Do you need a microcontroller that runs at 1 GHz? No, probably not. But that didn’t stop [Visual Micro] from trying, and the results are pretty interesting. Not only did the plucky little chip not cook itself, it actually seemed to run fairly well; with the already powerful microcontroller getting a considerable boost in performance.

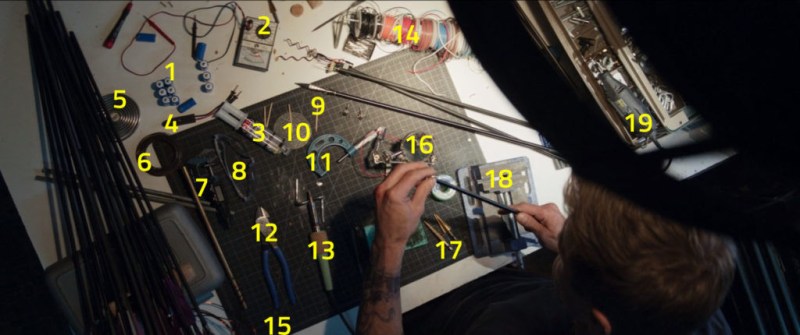

According to [Visual Micro] the Teensy 4.1, which normally has its ARM Cortex-M7 clocked at 600 MHz, can run at up to 800 MHz without any additional cooling. But beyond that, you’ll want to invite some extra surface area to the party. It’s easy enough to cut a chunk out of an old CPU/GPU cooler and stick it on with a dab of thermal compound, but of course there’s no shortage of commercially available heatsinks at this size that you could pick up cheap.

With the heatsink installed, [Visual Micro] shows the Teensy running at around 62 °C during a benchmark. If that’s a little hot for your liking, they also experimented with an old laptop cooler which knocked the chip down to an impressive 38 °C while under load. It doesn’t look like a particularly practical setup to us, but at least the option is there.

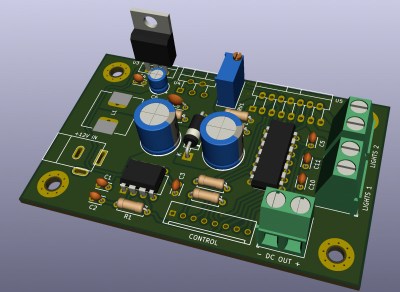

[Visual Micro] unfortunately doesn’t go into a lot of detail about the benchmark results, but from what’s shown, it appears the overclock netted considerable gains. A chart shows that in the time it took a stock Teensy to calculate 15.2 million prime numbers, the overclocked chip managed to blow through 21.1 million. The timescale for this test is not immediately clear, but the improvement is obvious.

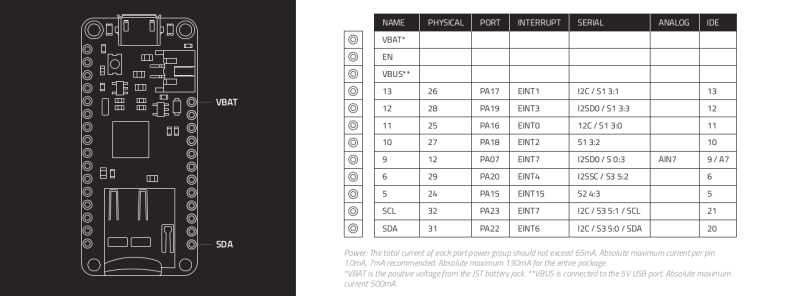

Even at the stock 600 MHz, the Teensy 4 is a very powerful MCU. Especially after the 4.1 refresh brought in support for additional peripherals and more RAM. But we suppose some people are never satisfied. Got a project in mind that could benefit from an overclocked Teensy? We’d love to hear about it.

Continue reading “Teensy 4 Pushed To The Limit With 1 GHz Overclock”