With the recent passing of Don Lancaster, I took a minute to reflect on how far things have come in a pretty short period of time. If you somehow acquired a computer in the early 1970s, it was probably some discarded DEC, HP, or Data General machine. A few people built their own, but that was a stout project with no microprocessor chips readily available. When machines like the Mark-8 and, more famously, the Altair appeared, the number of people with a “home computer” swelled — relatively speaking — and it left a major problem: What kind of input/output device could you use?

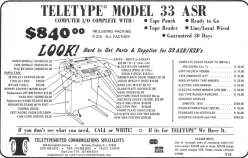

At work, you might have TeleType. Most of those were leased, and the price tag of a new one was somewhere around $1,000. Remember, too, that $1,000 in 1975 was a small fortune. Really lucky people had video terminals, but those were often well over $1,500, although Lear Siegler introduced one at the $1,000 price, and it became wildly successful. Snagging a used terminal was not very likely, and surplus TeleType equipment was likely of the 5-bit Baudot variety — not unusable, but not the terminal you really wanted.

A lot of the cost of a video terminal was the screen. Yet nearly everyone had a TV, and used TVs have always been fairly cheap, too. That’s where Don Lancaster came in. His TV Typewriter Cookbook was the bible for homebrew video displays. The design influenced the Apple 1 computer and spawned a successful kit for a company known as Southwest Technical Products. For around $300 or so, you could have a terminal that uses your TV for output. Continue reading “TV Typewriter Remembered”