If you are a science fiction fan, you probably hate the theory of relativity. After all, how can the Enterprise get to a new star system every week if you can’t go faster than the speed of light? [Nick Lucid] wants to set you straight: it is real, and you can prove it to yourself for under $100.

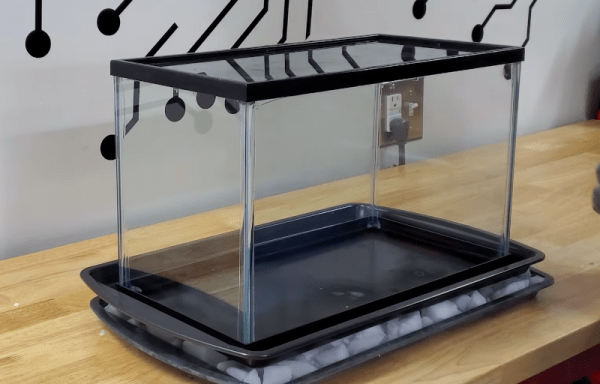

The idea uses muons created in our atmosphere by cosmic rays colliding with gasses in the atmosphere. So how do you detect muons yourself? [Nick] shows you how to do it with a fish tank, dry ice, and rubbing alcohol. If that sounds like a cloud chamber, you aren’t wrong.

A cloud chamber is undeniably cool, but how does it prove relativity? You’ll see several kinds of particles interacting with your cloud chamber, but you can tell which ones are muons by the size and motion of the streaks. The muons don’t last very long. So you’d expect very few muons to make it to the surface of the Earth. But they not only reach the surface but go deep under it, as well.

So how do you explain it? Relatively. The muon experiences its average 2.2 microseconds lifetime in what appears to us to be over 150 microseconds, even if it is moving relatively slowly for a muon. Some muons are faster or live longer, so we see a lot of them hit the Earth every minute of every day. This is due to time dilation and also explains length contraction because the muon moves at a certain speed, yet it appears to go further to us than to the muon.

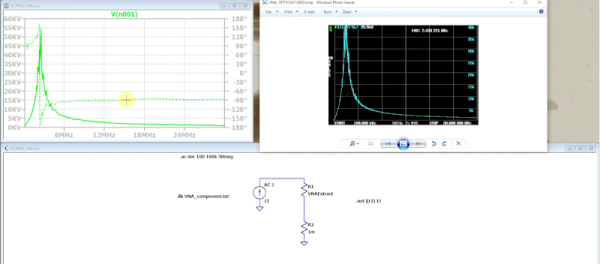

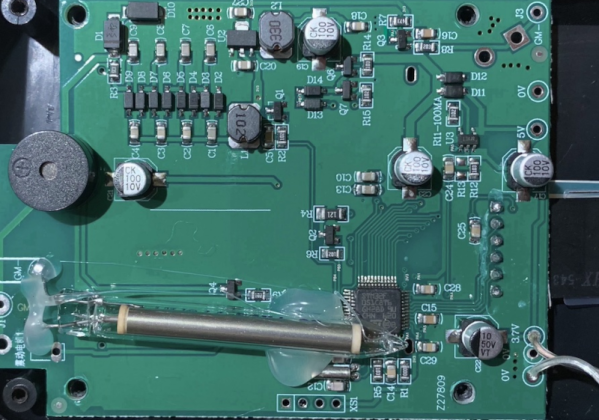

Coincidentally, we recently discussed this same effect relative to using muons for underground navigation. If you want an easier way to count muons with a computer, you can build a detector for about the same price as the cloud chamber.

Continue reading “Demo Relativity For A C-Note” →