Plasma cutters are ridiculously cheap these days, just cruise by the usual online sources or your local Harbor Freight if you’ve got any doubt about that. But “cheap” and “good” don’t always intersect on a Venn diagram, and even when they do, not every plasma cutter is suitable for use on the spanking new CNC table you’re building. But luckily, there’s a mod for that.

As [Jake von Slatt] explains it, there are two kinds of plasma cutters on the market: high-frequency (HF) start and pilot arc start. The basic difference is that HF start cutters, which comprise the majority of cheap cutters on the market, need direct electrical contact with the workpiece to start the cutting action. Pilot arc torches, which are more suitable for CNC cutters, can strike the arc through a separate conductor without the need to contact the workpiece.

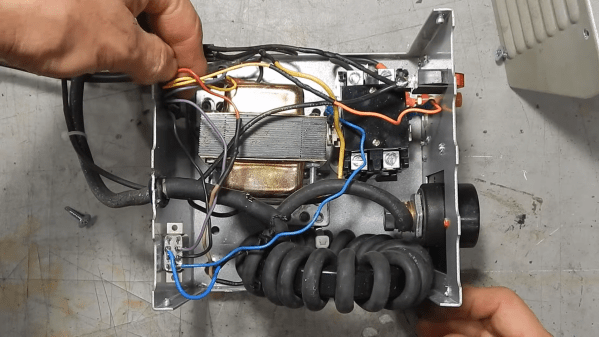

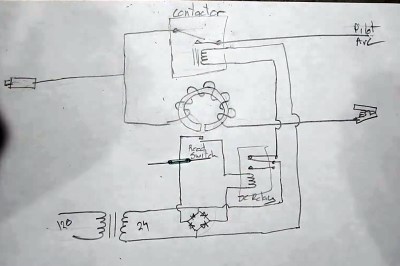

While there are homebrew bodges that claim to turn an HF torch into a pilot arc, [Jake]’s approach is a bit more complicated, and necessarily so. His add-on box intercepts the ground clamp — which is actually the positive conductor for plasma cutting — and switches it through a heavy-duty HVAC contactor. The 24 VDC coil of the contactor is controlled by a homebrew current sensor made from a huge toroid ferrite core wrapped with 20 turns of 6 AWG welding wire.

While there are homebrew bodges that claim to turn an HF torch into a pilot arc, [Jake]’s approach is a bit more complicated, and necessarily so. His add-on box intercepts the ground clamp — which is actually the positive conductor for plasma cutting — and switches it through a heavy-duty HVAC contactor. The 24 VDC coil of the contactor is controlled by a homebrew current sensor made from a huge toroid ferrite core wrapped with 20 turns of 6 AWG welding wire.

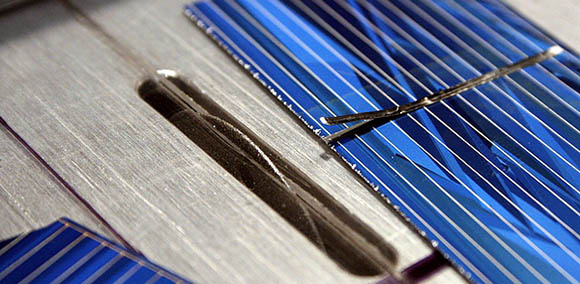

Before winding, the core is split in two and epoxied back together with a small magnetic reed switch bridging the gap. A simple 24 VDC power supply runs the whole thing. When the torch starts, the nozzle is connected to ground through the contactor, but as soon as the arc strikes and starts pulling cutting current through that toroid, the magnetic field closes the reed switch, which opens the contactor via a small DC relay. This removes the connection between the nozzle and ground, leaving the plasma to carry all the cutting current.

We’ve featured many, many CNC plasma cutter tables before, but most of these builds have concentrated on the table more than the cutter. It’s a refreshing change to get some insider tips on what kinds of cutters work best, and how to adapt what you’ve got for the job.

Continue reading “Simple Add-On Makes Cheap Plasma Cutter Suitable For CNC Use”