The round bottom of a proper wok is the key to a decent stir fry, but it also makes it hard to use on traditional Western stoves. That’s why many woks end up in a dark kitchen cabinet, unused and unloved. But wait; it turns out that the round bottom of a wok is the perfect shape for gathering something else — radio waves, specifically the 21-cm neutral hydrogen emissions coming from the heart of our galaxy.

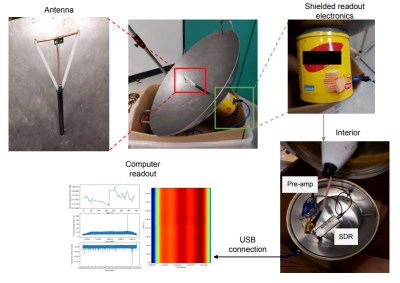

Turning a wok into an entry-level radio telescope doesn’t appear to be all that hard, at least judging by what [Leo W.H. Fung] et al detail in their paper (PDF) on “WTH” or “Wok the Hydrogen.” Aside from the wok, which serves as the main reflector, you’ll need a bit of coaxial cable and some stiff copper wire to fashion a small dipole antenna and balun, plus some plastic tubing to support it at the focal point of the reflector. Measuring the wok’s shape and size, which in turn determines its focal point, is probably the hardest part of the build; luckily, the paper includes tips on doing just that. The authors address the controversy of parabolic versus spherical reflectors and arrive at the conclusion that for a radio telescope fashioned from a wok, it just doesn’t matter.

As for the signal processing chain, WTH holds few surprises. A Nooelec Sawbird+ H1 acts as preamp and filter for the 1420-MHz hydrogen line signal, which feeds into an RTL-SDR dongle. Careful attention is paid to proper grounding and shielding to keep the noise floor as low as possible. Mounting the antenna is a decidedly ad hoc affair, and aiming is as simple as eyeballing various stars near the center of the galactic plane — no need to complicate things.

As for the signal processing chain, WTH holds few surprises. A Nooelec Sawbird+ H1 acts as preamp and filter for the 1420-MHz hydrogen line signal, which feeds into an RTL-SDR dongle. Careful attention is paid to proper grounding and shielding to keep the noise floor as low as possible. Mounting the antenna is a decidedly ad hoc affair, and aiming is as simple as eyeballing various stars near the center of the galactic plane — no need to complicate things.

Performance is pretty good: WTH measured the recession velocity of neutral hydrogen to within 20 km/s, which isn’t bad for something cobbled together from scrap. We’ve seen plenty of DIY hydrogen line observatories before, but WTH probably wins the “get on the air tonight” award.

Thanks to [Heinz-Bernd Eggenstein] for the tip.

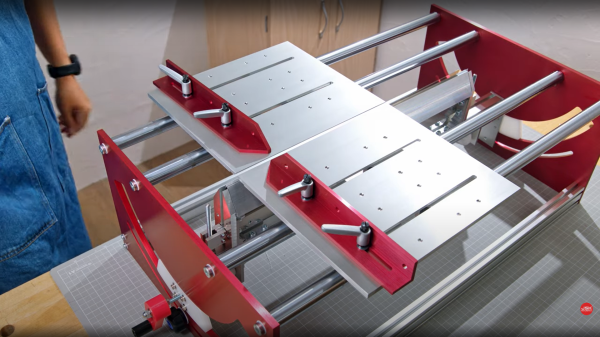

which might be a bit tricky to track down if you were so inclined to reproduce the build. It appears (well if you believe the auto-translation by Google Lens, anyway) to be a spare blade for a commercial guide saw available in Japan at least.

which might be a bit tricky to track down if you were so inclined to reproduce the build. It appears (well if you believe the auto-translation by Google Lens, anyway) to be a spare blade for a commercial guide saw available in Japan at least.