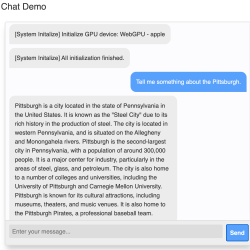

Large Language Models (LLM) are at the heart of natural-language AI tools like ChatGPT, and Web LLM shows it is now possible to run an LLM directly in a browser. Just to be clear, this is not a browser front end talking via API to some server-side application. This is a client-side LLM running entirely in the browser.

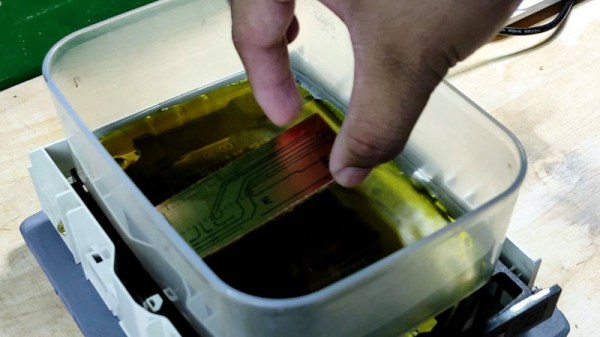

Running an AI system like an LLM locally usually leverages the computational abilities of a graphics card (GPU) to accelerate performance. This is true when running an image-generating AI system like Stable Diffusion, and it’s also true when implementing a local copy of an LLM like Vicuna (which happens to be the model implemented by Web LLM.) The thing that made Web LLM possible is WebGPU, whose release we covered just last month.

WebGPU provides a way for an in-browser application to talk to a local GPU directly, and it sure didn’t take long for someone to get the idea of using that to get a local LLM to run entirely within the browser, complete with GPU acceleration. This approach isn’t just limited to language models, either. The same method has been applied to successfully create Web Stable Diffusion as well.

It’s a fascinating (and fast) development that opens up new possibilities and, hopefully, gives people some new ideas. Check out Web LLM’s GitHub repository for a closer look, as well as access to an online demo.