When the internal rechargeable battery in his wireless mouse died, [cmot17] decided it was the perfect excuse for making a couple of modifications. The Logitech MX Master isn’t exactly a budget mouse to begin with, but that doesn’t mean there’s no room for improvement. With the addition of a larger battery and USB-C charging port, a very nice mouse just got even better.

As it turns out, there’s plenty of empty space inside the Logitech MX Master, which made it easy to add a larger battery. The original 500 mAh pack was replaced with a new 950 mAh one, which is often sold under the model number 603443. Realistically, if you wanted to go even bigger it looks like any three wire 3.7 V Li-Po pack would probably work in this application, but nearly doubling the capacity is already a pretty serious bump.

Adding the USB-C connector ended up being quite a bit trickier. [cmot17] ordered a breakout board from Adafruit that was just a little too large to fit inside the mouse. In the end, not only did some of the case need to get cut away internally, but the breakout PCB itself got a considerable trimming. Once it was shoehorned in there, a healthy dose of hot glue was used to make sure nothing shifts around.

Since [cmot17] didn’t change the mouse’s original electronics, the newly upgraded Logitech MX Master won’t actually benefit from the faster charging offered by USB-C. If anything, it’s actually going to charge slower thanks to the beefier battery. But considering how infrequently it will need to be charged with the upgraded capacity (Logitech advertised 40 days with the original 500 mAh battery), we don’t think it will be a problem.

Over the years, we’ve seen plenty of stuff crammed into the lowly mouse. Everything from a full computer, to malicious firmware code has been grafted onto that most ubiquitous of computer peripherals. So in the grand scheme of things, this is perhaps one of the most practical mouse modifications to ever grace these pages.

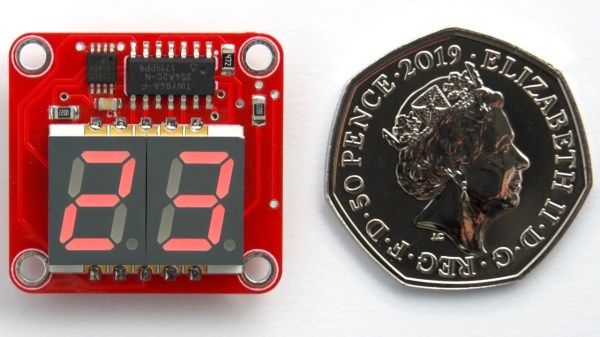

You may think that a display that flashes only once every 24 seconds might be difficult to actually read in practice, and you’d be right. [David] found that it was indeed impractical to watch the display, waiting an unknown amount of time to read some briefly-flashed surprise numbers. To solve this problem, the decimal points flash shortly before the temperature appears. This countdown alerts the viewer to an incoming display, at the cost of a virtually negligible increase to the current consumption.

You may think that a display that flashes only once every 24 seconds might be difficult to actually read in practice, and you’d be right. [David] found that it was indeed impractical to watch the display, waiting an unknown amount of time to read some briefly-flashed surprise numbers. To solve this problem, the decimal points flash shortly before the temperature appears. This countdown alerts the viewer to an incoming display, at the cost of a virtually negligible increase to the current consumption.

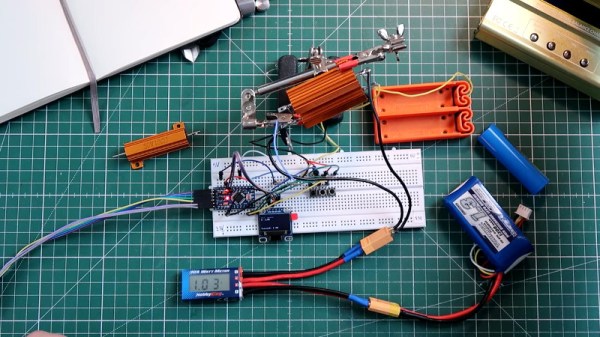

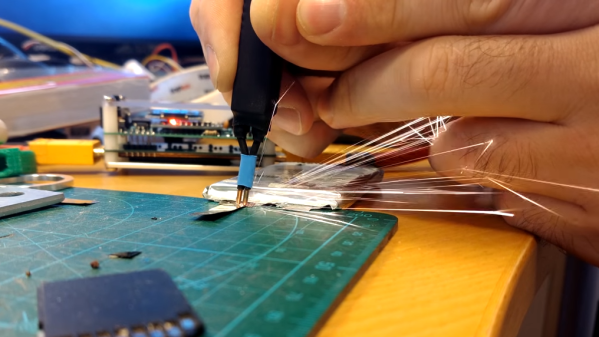

Did you ever see a thin metal tab bonded to a battery terminal with little pock marks? That’s the work of a spot welder. Spot welding is one of those processes that doesn’t offer much in the way of alternatives; either one uses a spot welder to do the job right, or one simply does without. That need is what led [Erwin Ried] to purchase a small, battery-powered spot welder from a maker in Korea and

Did you ever see a thin metal tab bonded to a battery terminal with little pock marks? That’s the work of a spot welder. Spot welding is one of those processes that doesn’t offer much in the way of alternatives; either one uses a spot welder to do the job right, or one simply does without. That need is what led [Erwin Ried] to purchase a small, battery-powered spot welder from a maker in Korea and