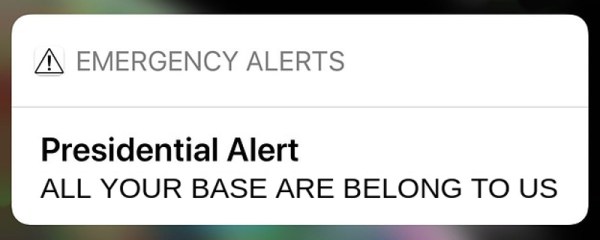

In April of 2018, the Federal Emergency Management Agency sent out the very first “Presidential Alert”, a new class of emergency notification that could be pushed out in addition to the weather and missing child messages that most users were already familiar with. But while those other messages are localized in nature, Presidential Alerts are intended as a way for the Government to reach essentially every mobile phone in the country. But what if the next Presidential Alert that pops up on your phone was actually sent from somebody with a Software Defined Radio?

According to research recently released by a team from the University of Colorado Boulder, it’s not as far-fetched a scenario as you might think. In fact, given what they found about how the Commercial Mobile Alert Service (CMAS) works, there might not be a whole lot we can even do to prevent it. The system was designed to push out these messages in the most expedient and reliable way possible, which meant that niceties like authentication had to take a backseat.

The thirteen page report, which was presented at MobiSys 2019 in Seoul, details their findings on CMAS as well as their successful efforts to send spoofed Presidential Alerts to phones of various makes and models. The team used a BladeRF 2.0 and USRP B210 to perform their mock attacks, and even a commercially available LTE femtocell with modified software. Everything was performed within a Faraday cage to prevent fake messages from reaching the outside world.

The thirteen page report, which was presented at MobiSys 2019 in Seoul, details their findings on CMAS as well as their successful efforts to send spoofed Presidential Alerts to phones of various makes and models. The team used a BladeRF 2.0 and USRP B210 to perform their mock attacks, and even a commercially available LTE femtocell with modified software. Everything was performed within a Faraday cage to prevent fake messages from reaching the outside world.

So how does the attack work? To make a long story short, the team found that phones will accept CMAS messages even if they are not currently authenticated with a cell tower. So the first phase of the attack is to spoof a cell tower that provides a stronger signal than the real ones in the area; not very difficult in an enclosed space. When the phone sees the stronger “tower” it will attempt, but ultimately fail, to authenticate with it. After a few retries, it will give up and switch to a valid tower.

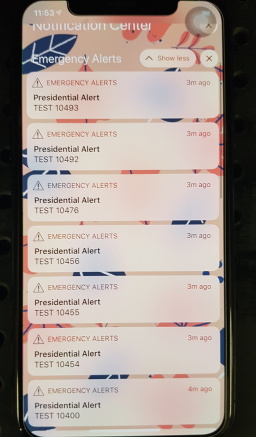

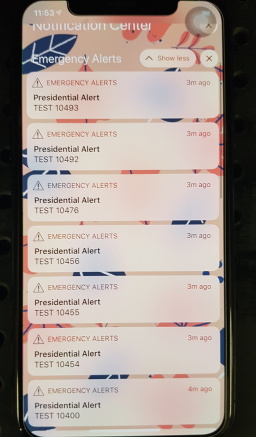

This negotiation takes around 45 seconds to complete, which gives the attacker a window of opportunity to send the fake alerts. The team says one CMAS message can be sent every 160 milliseconds, so there’s plenty of time to flood the victim’s phone with hundreds of unblockable phony messages.

The attack is possible because the system was intentionally designed to maximize the likelihood that users would receive the message. Rather than risk users missing a Presidential Alert because their phones were negotiating between different towers at the time, the decision was made to just push them through regardless. The paper concludes that one of the best ways to mitigate this attack would be to implement some kind of digital signature check in the phone’s operating system before the message gets displayed to the user. The phone might not be able to refuse the message itself, but it can at least ascertain it’s authentic before showing it to the user.

All of the team’s findings have been passed on to the appropriate Government agencies and manufacturers, but it will likely be some time before we find out what (if any) changes come from this research. Considering the cost of equipment that can spoof cell networks has dropped like a rock over the last few years, we’re hoping all the players can agree on a software fix before we start drowning in Presidential Spam.