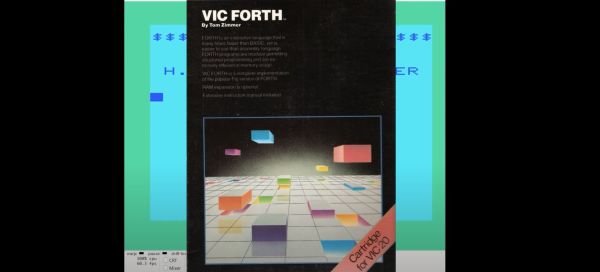

Although BASIC was most commonly used on home computers like the Commodore VIC-20, it was possible to write programs in other languages, such as Forth. Conveniently, all it took to set up a Forth development system was inserting the cartridge into the VIC-20 and powering it on, with the VIC-FORTH cartridge by [Tom Zimmer] being a popular choice for the Commodore VIC-20. In a recent video, the [My Developer Thoughts] YouTube channel covers Forth development using this cartridge.

In addition to the video tutorial, the original VIC-FORTH Instruction Manual is also available, together with the 1541 disk image. In an upcoming video, the Commodore 64 version of the cartridge will also be covered, which is called 64Forth, and which is also readily available to tinker with. For those interested in learning more about [Tom Zimmer] and his Forth-related work, a 2010 interview could be interesting. This covers the other platforms which he developed an implementation for.

As for why Forth might be interesting to developers and users, this comes mostly down to the much lower overhead of Forth compared to BASIC, while avoiding the pitfalls of ASM and resource-intensive nature of developing in C, as the entire Forth development system (compiler, editor, etc.) comfortably fits in the limited memory of the average 8-bit home computer.

(Thanks to [Stephen Walters] for the tip)