[Erich] is the middle of building a new competition sumo bot for 2018. He’s trying to make this one as open and low-cost as humanly possible. So far it’s going pretty well, and the quest to make DIY parts has presented fodder for how-to posts along the way.

[Erich] is the middle of building a new competition sumo bot for 2018. He’s trying to make this one as open and low-cost as humanly possible. So far it’s going pretty well, and the quest to make DIY parts has presented fodder for how-to posts along the way.

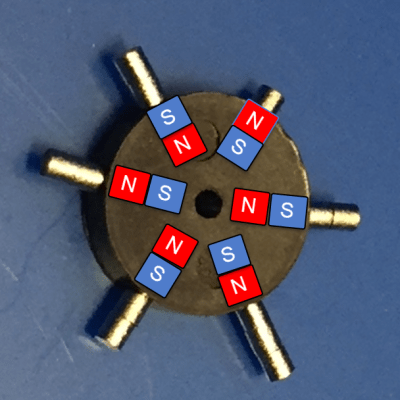

One of new bot’s features will be magnetic position encoders for the wheels. In the past, [Erich] has used the encoder disks that Pololu sells without issue. At 69¢ each, they don’t exactly break the bank, either. But shipping outside the US is prohibitively high, so he decided to try making his own disks with a 3D printer and the smallest neodymium magnets on Earth.

The pre-fab encoder disks don’t have individual magnets—they’re just a puck of magnetic slurry that gets its polarity on the assembly line. [Erich] reverse-engineered a disk and found the polarity using magnets (natch). Then got to work designing a replacement with cavities to hold six 1mm x 1mm x 1mm neodymium magnets and printed it out. After that, he just had to glue them in place, matching the polarity of the original disk. We love the ingenuity of this project, especially the pair of tweezers he printed to pick and place the magnets.

Rotary encoders are pretty common in robotics applications to detect and measure wheel movement. Don’t quite recall how they work? We’ll help you get those wheels turning.